Home invasion films are undoubtedly a lasting source of sporadic dread for moviegoers, with their realism serving to heighten the sense of vulnerability that these scenarios, although made up, evoke. The intrusion into one’s sanctuary—the very place where one should feel secure—during the domineering darkness of night, represents a deeply entrenched fear. But what happens when such a nightmare transpires in broad daylight?

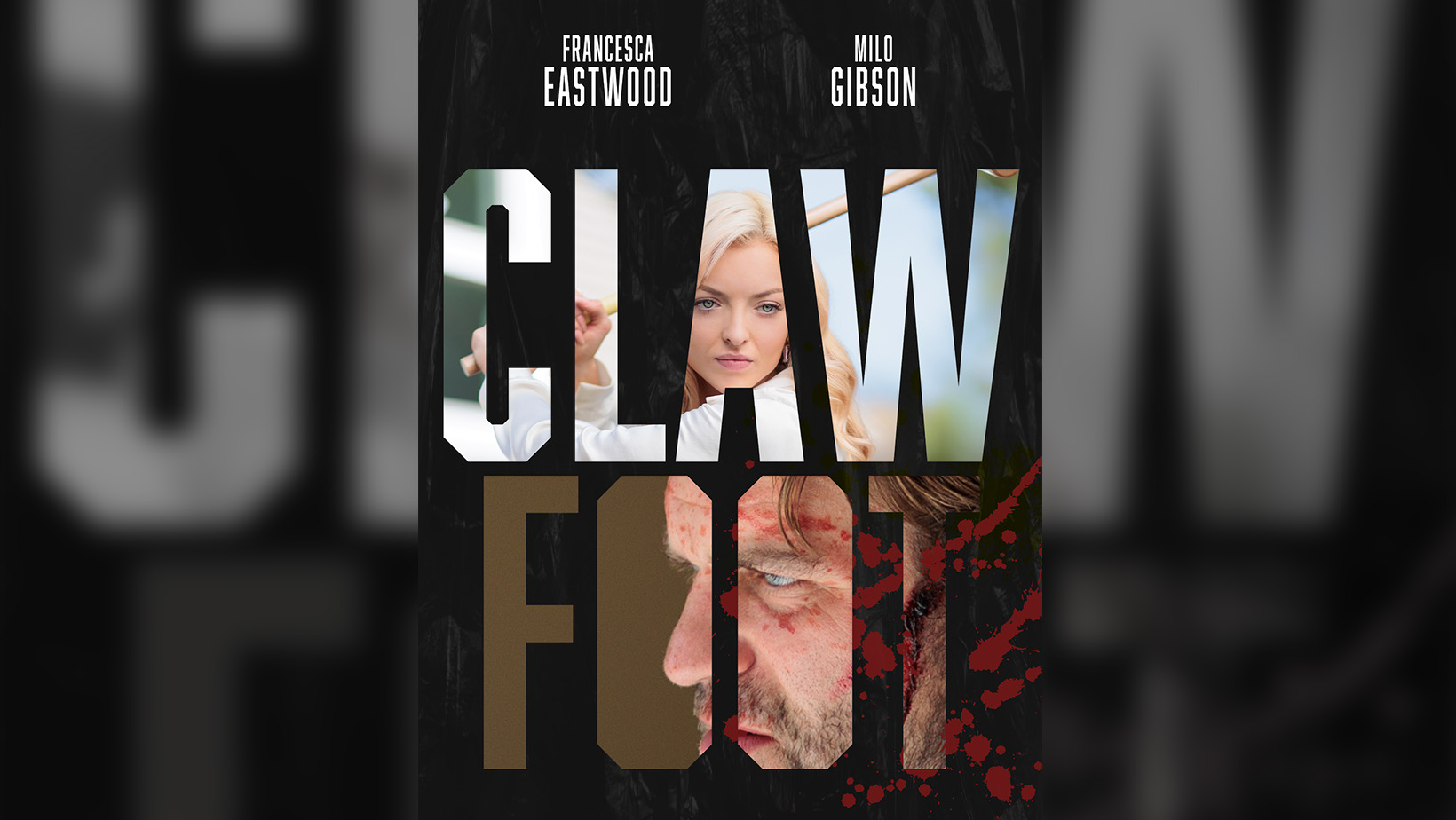

Michael Haneke’s Funny Games has already delved into this unsettling premise, demonstrating how a daytime home invasion can turn an ordinary scenario into a harrowing experience. In a similar vein, Clawfoot, the feature debut of Michael Day, revisits this concept, reigniting fears of daylight terror—at least temporarily.

In Clawfoot, Francesca Eastwood, daughter of Clint Eastwood, stars as Janet, an affluent stay-at-home wife who finds herself tormented by a scheming contractor, Leo, played by Milo Gibson, son of Mel Gibson. Leo has been hired to remodel Janet’s bathroom, but what begins as an unexpected renovation soon devolves into psychological warfare. The film becomes a tense contest of mind games as both characters vie to assert their dominance within the confines of Janet’s home.

The film’s strength lies significantly in the performances of Eastwood and Gibson. Both of them played their parts really well, with Eastwood’s effortless posh and Gibson’s charismatic yet menacing demeanour, creating a compelling contrast that would make you ask how things will work out along the way. Their interplay keeps viewers on edge, as the tension mounts over how long their façades will endure before one character’s true intentions are revealed.

Their eerie psychological tug-of-war in Clawfoot is arguably the film’s most engaging bit. Both characters meticulously avoid straightforward approaches to achieve their goals, leading to a prolonged psychological struggle. We get to wonder about it too, until later on in the film. The series of intrigue in the first half of the game gets too real as they anticipate which character will falter first.

However, like what was said earlier, all of this intrigue is temporary as the film’s second half takes an unexpected turn, shifting from a gripping psychological drama to a horror-comedy. This transition diminishes the intensity and suspense that had been meticulously built. The humor introduced does little to enhance the narrative, and Oliver Cooper’s character Samuel emerges as a rare exception, providing comic relief with his eccentric and incongruous personality.

The tonal shift is further accentuated by a very unserious soundtrack that clashes with the film’s earlier suspenseful atmosphere. The decision to employ such a soundtrack appears ill-conceived, undermining the film’s attempts to maintain a cohesive mood.

On another note, Clawfoot subtly explores how the pursuit of power can overwhelm individuals, revealing how those in positions of privilege can turn people—regardless of their social class—into collateral damage in their efforts to preserve their status. However, the true horror of the film lies in how misdeeds like these could be done as easily as it is said by these people.

Fortunately, it never had a dull moment throughout its brisk runtime of approximately ninety minutes. For those seeking a worthy new entry for the home invasion genre, Clawfoot offers a brief but considerable experience.

Clawfoot will be available on Digital Download from 23rd September.

More Film Reviews

Junk Head is a 2017 dystopian stop-motion animation film, written and directed by Takahide Hori. The film is based on the director’s 2013 first short film Junk Head 1, whose… The Maid takes place in a sumptuous mansion, where Joy is the most recent maid in a high-turnover position. Upon her first introduction, she learns the rules of the house,… The strength of the Japanese independent cinema has often rested on its ability to embrace absurdity and bring it together in a distinct yet cohesive manner. Consequently, the intuitive approach… When a journalist has the breaking story of a lifetime, he discovers all is not well. Not only is there the looming threat of powerful people who may squash him… To me, Justin Russell is quite the underrated horror filmmaker, whose love for the genre shows in his work, such as the ’80s slasher homage, “The Sleeper” (2012). I wanted… I honestly haven’t had this much “fun” while watching a horror movie in quite a long time. Shudder release Vicious Fun is true to the name; it carries immense nostalgic…Junk Head (2017) Film Review – Superb Stop-Motion Cinema

The Maid (2021) Film Review – Thai Horror at FrightFest

Yellow Dragon’s Village (2021) Film Review – Low Budget Insanity

The Eyes Below (2022) Film Review – They Are Watching You

DEATH STOP HOLOCAUST (2009) Film Review: Decent TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE Homage

Vicious Fun (2020) Film Review – An Aptly Titled Horror Comedy

I am a 4th year Journalism student from the Polytechnic University of the Philipines and an aspiring Filmmaker. I fancy found footage, home invasions, and gore films. Randomly unearthing good films is my third favorite thing in life. The second and first are suspending disbelief and dozing off.