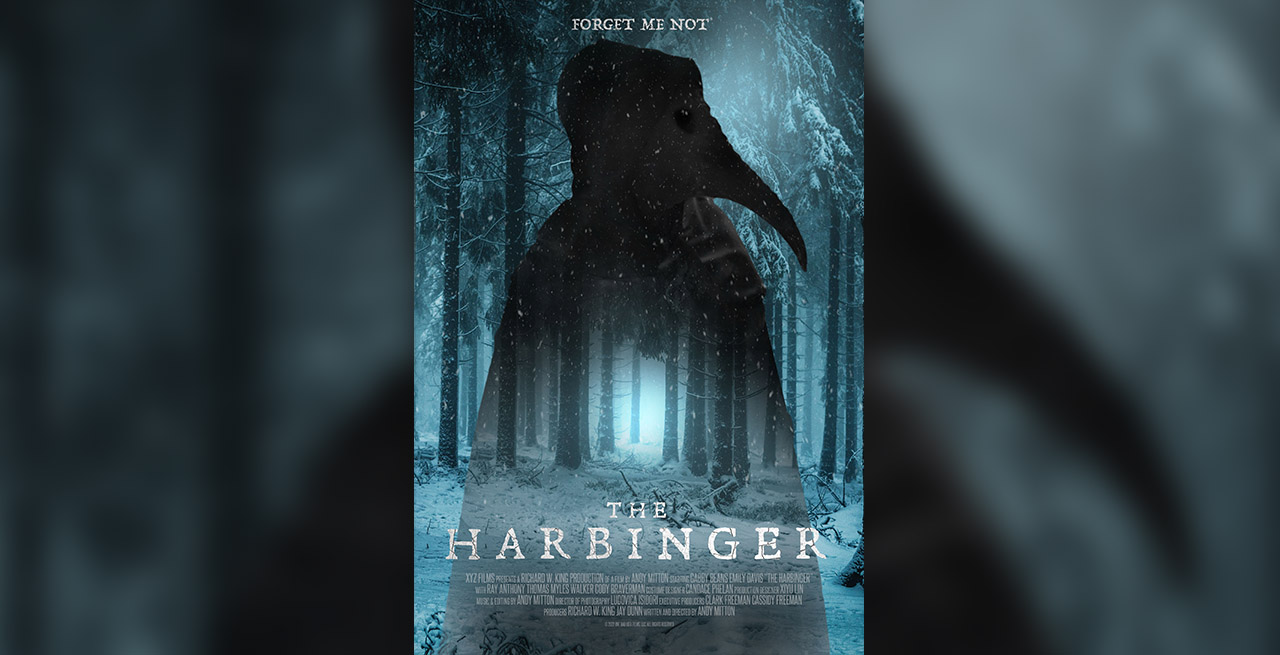

The Harbinger, Andy Mitton’s follow-up to his delightfully creepy Witch in the Window, is, simply put, the most terrifying COVID-era horror film. Dealing with many of Mitton’s signature themes – the loss of a loved one and what remains after death – the movie is one uninterrupted, unrelenting nightmare that amplifies the viewer’s pandemic fears to unbearable levels. Imagining a new disease that slowly erases its victims from the world, The Harbinger cleverly mixes isolation metaphors and old-school supernatural horror in one of the year’s most sobering watches.

A film about enduring hope in the face of insurmountable tragedy, Mitton’s latest opens with the image of a cherub and the sound of a lullaby. After briefly witnessing the sight of an ominous plague doctor and hearing the words “not ready to be forgotten”, the viewer is transported to the home of Monique, currently surviving the pandemic with her father and brother in strict isolation. When her friend Mavis calls, Monique decides to break quarantine and help her out. Mavis, living in an apartment building with the threat of COVID ever looming, also suffers from a dream-sickness, finding it more and more difficult to wake up after encountering a plague doctor-like entity and constantly dying in her own nightmares.

In the beginning, the movie sets its few pieces on the board, with talks about the responsibility of staying indoors, not bringing the virus to your loved ones, and a comforting conversation about smells. Soon, this safety is broken by coughs, paranoid glances, and COVID deniers yelling the word “sheeple” at the mere sight of a mask. Keeping a two-feet distance, people blame the less cautious for spreading the sickness, the sudden siren sounds too close for comfort, and the new division over social responsibility. A mostly unknown threat that could claim the immuno-deficient at any time. Mitton conjures the modular existentialism of 2020 all too well, and later adds a new layer around the concept of virus immunity, imagining the more prone to the plague doctor’s killing influence as lonely people.

Those who lack friends, those with poor “people skills”, the ones who had been living in isolation long before the pandemic. Those with no living relatives, are more likely to be easily forgotten. Mavis only has Monique to remember her, but after she learns what kind of sickness her friend is facing (a plague that can erase her from the world entirely) and that it might be contagious, Monique has the choice of staying loyal or running back to her loved ones.

In a setup that starts to resemble “nursing horror” films like The Hexecutioners or the cult favorite Horsehead, Mitton makes Monique experience what Mavis is describing all too clearly. Her fear opens the door to an evil entity that preys on anxiety and extends it to the point of suffocation, blurring the lines between reality and dream. A boy falls through the ceiling and destroys the carefully isolated area the two women had been guarding. Later, he turns out to be an angel-like figure, perhaps the only key to keeping the entity at bay. Mitton associates Monique with the sparrow, a symbol of hope, and caring for others, but also a death omen in some cultures.

A study by Holt-Lunstad reveals that loneliness, living alone and poor social connections are worse for your health than smoking 15 cigarettes a day, worse than obesity, and associated with a high risk of heart disease and strokes. Loneliness is a silent killer, and above all, the movie’s plague doctor adversary is a metaphor for loneliness. It spreads itself like a bad idea, and no one wants to hear you say its name – just like in real life, lonely people often tire their peers out with their depressing accounts, taking them out of their happy place. Loneliness divides, loneliness is bad company. Long forgotten is the Existentialist motto that “Hell is other people” – the real horror behind The Harbinger might be the implication that one must be around other people in order to survive, constantly nurture their social connections, and water them like high-maintenance plants, especially if they have no living relatives.

The other scary aspect isn’t an implication at all, it’s the fear of being forgotten we all share, very similar in shape to the fear of ending up a complete failure in life. Athazagoraphobia is the word. Only when reading about this fear, it becomes clear that The Harbinger could be a movie about the realities of living with Alzheimer’s, as well as taking care of someone who has it. What’s scarier: the possibility of forgetting yourself or a loved one forgetting about you? And what if the whole world was hit with a viral version of Alzheimer’s disease?

Remember when every film director made isolation testimonials during the 2020 lockdown? Netflix released Homemade, an anthology containing short films by Maggie Gylenhaal, Kristen Stewart, Pablo Larrain, and Ana Lily Amirpour. HBO released At Home, an international series featuring efforts by Leticia Dolera, Rodrigo Sorogoyen, Malgorzata Szumowska, and Mika Kurvinen. At Home persists, but Homemade was removed by Netflix at the end of 2021. Perhaps they were trying to erase the bad memories, offer a clean slate after a hellish two years?

The Harbinger offers no such respite. It is one of the few films – even more than Shelter in Place or We Have to Do Something or When I Consume You – that acknowledges that the world has been fractured, perhaps beyond repair, and that it’s only going to get worse from here on. Even the sporadic mentions of hope and keeping faith look like faint gestures of hopelessness. Richard Linklater would have been horrified if someone had pitched him the idea for The Harbinger while he was making the iconic Waking Life, two decades ago. In that movie, lucid dreams were an oasis – in Mitton’s, becoming aware is often associated with a fall. When you die, you still don’t wake up. You stay dead for hours, as well as being aware of yourself being dead, and the fact that it’s a dream. Time passes, you try everything you can to wake up, and when you do, you’re traumatized and barely able to transition to the waking world. And it’s only to get worse the next time you fall asleep, and worse, and worse, until eventually…

Even Neil Gaiman, the creator of The Sandman, an author who imagined a similar dream-sickness in the first volume of his seminal graphic novel series, would stop and pause at the implications. The only COVID-era movie that even remotely comes close to what Harbinger manages to achieve are Marc Munden’s Help, which depicted what the early days of the pandemic were like for nursing homes, and Hall, Francesco Giannini’s horror film which captured the despair of slowly dying from suffocation caused by lung disease. Had it been released before the pandemic, Hall would have been forgotten in no time, but in 2020, it amplified the viewer’s anxiety much like The Harbinger does with its sickness.

To make the experience even more devastating, Mitton makes the process of “being erased” an imperfect one: yes, nobody will remember you existed, but vestiges of human life always remain – a photo might contain a person no one remembers, a post-it on a fridge might make people wonder who wrote it, a drawing might trigger a memory long buried. Of course, Mitton doesn’t have to do that much, when the world is very keen on providing horror on a daily basis nowadays: Oxford researchers have recently discovered that common viruses might play a role in cases of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Ultimately a film that pulls no punches, asking the viewer “how easily forgettable are you?”, facing them with the possibility of a hope-shattering adversary that doesn’t forgive, that thrives in isolation and division, The Harbinger is an unforgettable experience, albeit one you won’t probably want to repeat very soon. Mitton wears multiple hats, also editing and providing the excellent music for the film, and based on this one’s immense power, its graph-like careful metaphors, and cautionary-tale conclusions, one might wonder just what this director – one who chooses personal stories with devastating, far-reaching implications in an increasingly postmodern world – will surprise us with next.

We watched The Harbinger (2022) at FrightFest

Past Festival Coverage

Incredible But True (2022) Film Review – Time Travel at its Most Inconvenient

Director Quinten Dupieux has been building a catalog of films ever since his release of Steak back in 2007. (However, you could argue he defined his image starting all the…

Deadly Games (1982) Film Review – Low-Key Slasher That Slipped Under the Radar

If you ask a casual movie goer to list some classic horror films, a large majority of them will mention Halloween, Friday the 13th, and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. One…

TADFF 2023 Canadian Short Film Feature [Toronto After Dark Film Festival]

In addition to those that played ahead of the main features, the Toronto After Dark Film Festival screened eight more Canadian shorts in a dedicated showcase. From rotoscope animation to…

Luzifer (2021) Film Review – Religious Fervor and Unforgiving Isolation

“Every day we stray further from God’s light” may be a ‘meme-able’ saying, but it is one that is none-the-less true when we look at a mix of contempt and…

The Unburied Film Review – Sins of the Father

Alejandro Cohen Arazi’s debut film The Unburied, was selected as part of the 2021 FrightFest lineup. Offering up a dive into a world of the occult built up through generations…

Yakuza Princess (2021) Film Review – Classic Yakuza Action with a Fresh Perspective

There is probably no better place to start discussing Yakuza Princess than with its setting of Sao Paulo, Brazil. As the film quickly points out in its introduction, Sao Paulo…

![TADFF 2023 Canadian Short Film Feature [Toronto After Dark Film Festival]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Untitled-design-18-365x180.jpg)