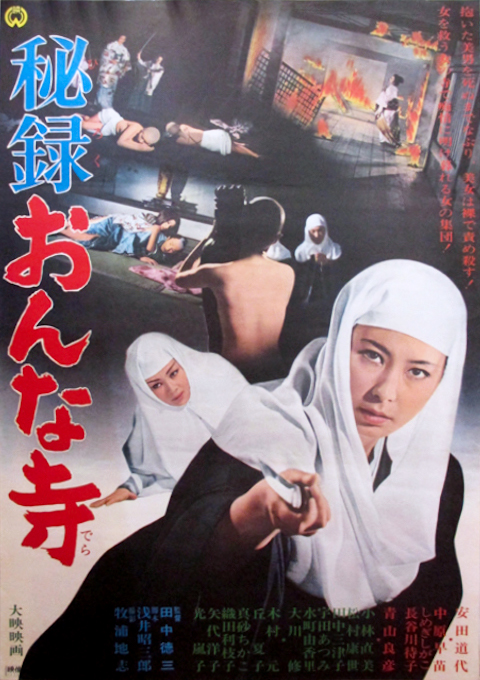

Despite being one of Japan’s biggest film studios throughout the late 40s and 50s during the golden age of Japanese cinema, Daiei was struggling by the mid-60s and had to slash budgets for their productions. This eventually led to a merger with Nikkatsu in 1970, followed by bankruptcy in 1971. Somewhat overlooked is Daiei’s 1968-1969 period where they started to focus on exploitation films and could be considered as their own equivalent to “pinky violence“. This era of exploitation, dubbed by Daiei as their “ero guro/unique historical drama” line, was largely defined by two film series: the Woman’s Secret series and the Kanto Woman series.

The Woman’s Secret series kicked off this new line with a focus on historical-set exploitation films, the first being Secrets of a Woman’s Prison in 1968. The fourth film in the series, Secrets of a Woman’s Temple, is set in the Horeki era of the mid-18th century and focuses on an all-female Buddhist convent. The film also acts as somewhat of a spiritual sequel to Daiei’s prior film The Daring Nun (1968) with some of the main cast members returning.

Because of how obscure this film is, Rob has outlined the plot below. If you want to avoid spoilers, skip down to the “Spoilers end here” tag below.

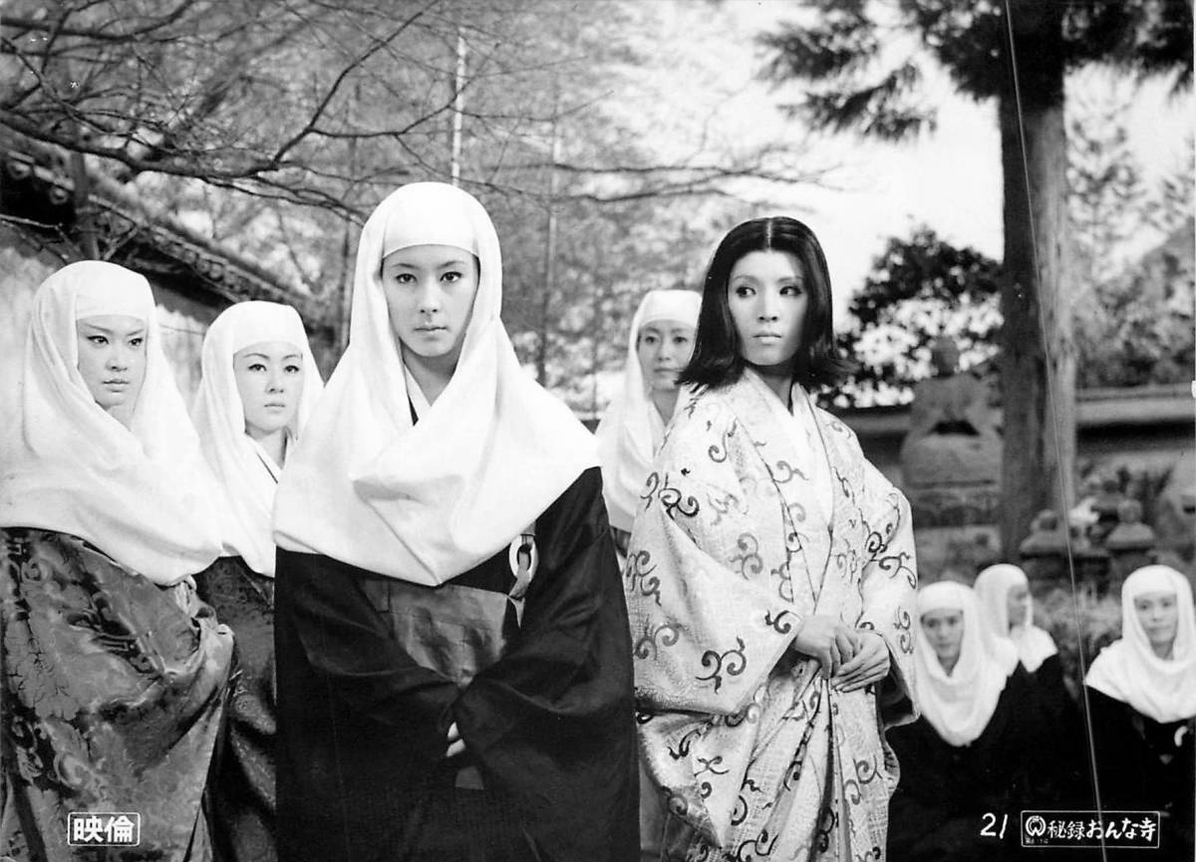

When a young woman, Oharu (Michiyo Yasuda), flees from the local constable, she takes refuge in the town’s Buddhist convent. After begging for shelter, the nuns agree to take her in as long as she renounces her sinful ways and becomes part of their order. Oharu, after accepting these conditions, must then meet the entire congregation and their priestess to be approved. Kneeling in the centre of the convent’s nun population, she is greeted by the monzeki (Shigako Shimegi) who is part of the powerful Tokugawa lineage. After the monzeki asks her if she is prepared to do anything to join the congregation, she then shocks Oharu by ordering her to kiss her foot – certainly not typical Buddhist behaviour. Oharu overcomes the embarrassment and obeys, only to be met with the monzeki’s cackle of contemptuous amusement which echoes through the silent room as the nuns make no attempt to challenge her bizarre actions.

Now accepted into the convent, she dons the nun’s habit and her head is shaved, but she has one final travail the following day in order to become a fully-fledged nun. She must perform a ceremonial marriage to the Buddha, but this is where the true unorthodoxy of the convent is exposed. After taking her vows at the foot of a life-size Buddha statue, the monzeki says that she must now consummate the marriage and orders her to remove her habit. Frozen in shock and disgust, Oharu eventually relents and embraces the statue. She is then instructed to use the statue to achieve orgasm in front of the entire congregation as they chant. All the while, the monzeki stands facing Oharu making no attempt to hide her lechery, her chest heaving as she stares on in depraved lust.

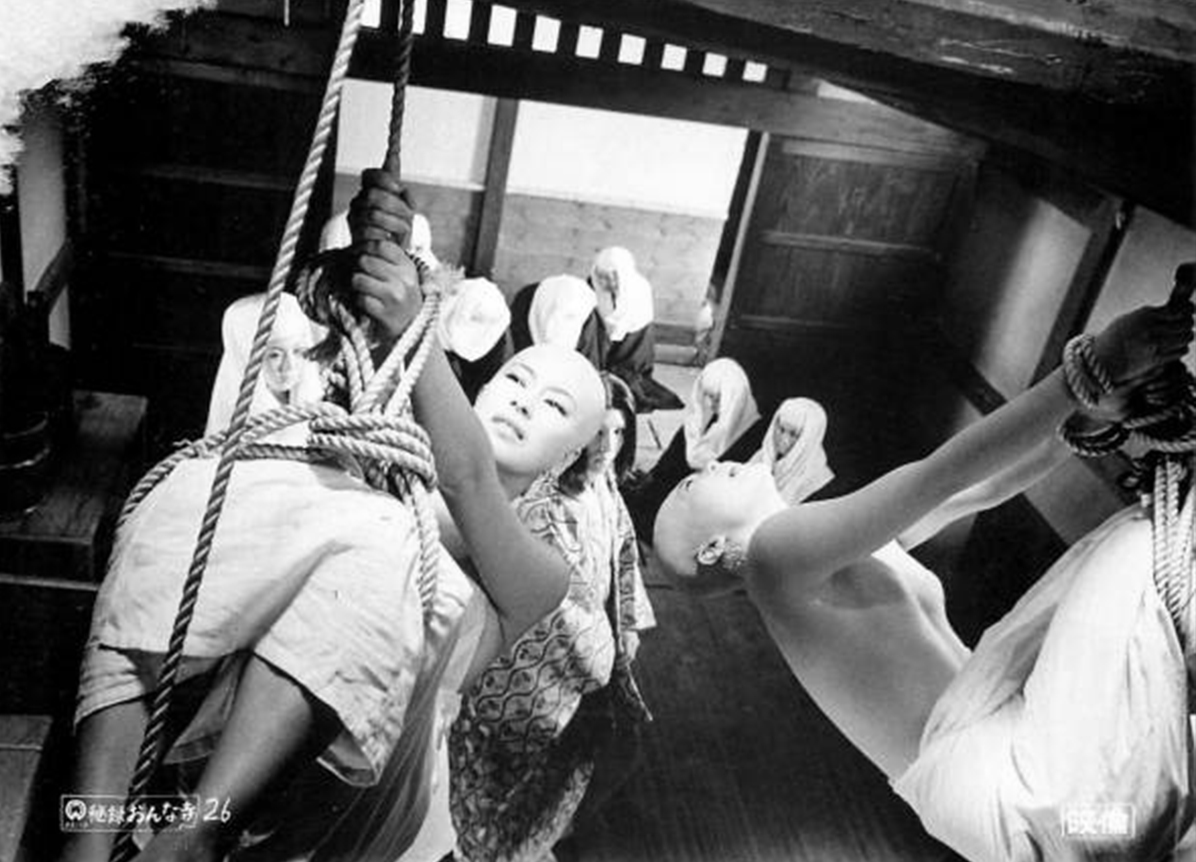

It is not long before the monzeki’s true nature as a sadistic tyrant is exposed, with any minor transgression met by extreme punishment, delivered personally by her own hand. She delights in humiliating and sexualised torture as the nuns are often forcibly stripped, bound, and flogged – all with maniacal glee. Now that she is a true member of the congregation, we find out that Oharu’s initial passive timidness was merely an act and she has an ulterior motive for joining the convent. Oharu’s brother disappeared and she heavily suspects that the monzeki was responsible for this, and perhaps even his murder; after learning the monzeki’s true nature, her suspicions are all but confirmed.

In order to investigate the monzeki further, Oharu must use her all wiles to gain access to the temple’s inner sanctum and eventually has to rely on the seduction of one of the senior nuns who is a lesbian. Oharu eventually discovers the extent of the monzeki’s sinfulness: not only has she allowed a man into the convent, but she is also keeping him as her personal lover. Later when one of Oharu’s friends becomes sick and is unable to chant, the monzeki’s whipping of her is so severe that she kills her. Now that the stakes are raised and the full danger of her situation is exposed, Oharu realises that she must act fast lest she suffers a similar fate. After failing to rally her fellow nuns to stage an insurrection, she bravely makes a desperate attempt to search the monzeki’s personal chambers.

When she is caught, the monzeki has her tied up and thrown in a cell which may very well end up becoming her final resting place. Fortunately, she is able to use a candle to break her bonds and escape before finding a private shrine in the inner sanctum. Upon opening it, her fears are confirmed as she finds a memorial plaque for her brother. The mother superior, perhaps wanting to clear her conscience, reveals to Oharu that she witnessed the monzeki beating her brother; when he tried to fight back, she grabbed a knife and savagely stabbed him to death. Incensed with rage, Oharu now tears through the convent in a mission of furious revenge.

***Spoilers end here!***

Secrets of a Woman’s Temple is clearly a fairly low-budget affair, taking place entirely within the small convent set. However, this becomes an advantage to film as the sparse and cramped surroundings bring an intense feeling of oppression and claustrophobia throughout; the nuns never leave the confines and the only outdoor scenes take place in the small garden area. The convent eventually ends up feeling almost like a prison due to this, which in many ways it is. Director Tokuzo Tanaka further enhances this feeling through his clever use of single-shot scenes, favouring the panning across a room, highlighting just how enclosed the women are.

It is also a film that embraces its black-and-white presentation and greatly benefits from it. Historically, a nun’s habit is desaturated black and white to show repentance and simplicity; the entire film being monochrome further builds on these themes of sacrifice and penitence as a result. From a purely visual standpoint, the lack of colour also amplifies the eeriness of the setting with rooms only illuminated by candlelight: the flames licking past the shoji, casting shadows that bring to mind the bars of a prison. Night scenes where Oharu is so often sneaking around feel fraught and tense as the nuns have to rely entirely on torches. The night is also the time when true sin comes alive. The phrase ‘hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil’ is alive and well as the pitch darkness hides a multitude of sins. Cloaked in the night, the convent quickly becomes a hotbed of forbidden passion and exploitation.

One unique aspect of the film within the nunsploitation genre is how refreshingly reserved it is, choosing not to rely on sleaze to provide a shock factor. Most films in the same genre verge on pornographic levels when dealing with the subject matter; certainly the most famous Japanese nunsploitation film School of the Holy Beast is almost totally reliant on nudity and sex to sell its sacrilegious and salacious status. On the other hand, Secrets of a Woman’s Temple lets its own actions speak for itself; the extremity and taboo nature of the events are more than enough to compliment this tale of sin without resorting to cheap thrills. The lesbianism in the film is also handled with an atypical degree of respect and restraint, taking time to really explore and understand the feelings and motivations of its characters, rather than just using it to tick off another juvenile porn fantasy. Similarly, the film doesn’t feel the need to denigrate homosexuality and makes a point of showing positive and consensual lesbian relationships rather than focusing on purely exploitation viewpoints.

Michiyo Yasuda shines in the film as a strong and likable heroine, managing to inject a measured degree of charisma into the usually solemn character of a nun. Her initial portrayal of the weak and vulnerable Oharu is incredibly convincing and easily manages to fool both the congregation and the audience of her true nature. Despite these strengths, it has to be said that much of the film belongs to Shigaki Shimegi. As an accomplished stage actress, Shimegi uses all her skills as she throws herself headfirst into the role of the nameless monzeki, totally embracing the lunacy of the character without letting her portrayal stray into pantomime. It would certainly be an easy part to both overact and underact, but she treads the line sublimely with her venomous line delivery, wildly callous gaze, and, of course, her deranged temper. Much of her character’s strength comes with her unpredictability: her opium-addled brain leaves her in a constant state of madness and emotional imbalance. She is a slave to desires and easily snaps without warning, very much embodying the praying mantis who will readily tear off the head of its mate.

Given the setting and subject matter, it is admittedly difficult not to compare it to other films tackling similar themes. Certainly, with its focus on temptation and an ever-constant air of forbidden passion, Black Narcissus frequently comes to mind while viewing. This comparison, unfortunately, serves to highlight the main shortcoming of the film: its lack of psychological exploration. Whilst the film does a great job delving into the results of pent-up lust, temptation, sadism, and hatred, no time is really spent looking deeper into its characters’ psyches. Oharu is an excellent heroine, though at times comes across as too infallible. We are shown the torment she receives but never how it affects her emotionally; the same applies to the rest of the characters. We clearly see how the nuns suffer, but what is the state of their mental health? What are their true thoughts? Perhaps the one character begging for greater attention is the monzeki who, after her initial introductions, is eventually relegated to a simple villainess role. The film’s short 79-minute runtime never truly allows any proper depth beyond the main story, with Oharu’s investigations and revenge mission given the main focus of proceedings.

Nevertheless, Secrets of a Woman’s Temple is a taut and effective thriller of sin and revenge that keeps its cards close enough to its chest throughout, ensuring that the audience is ever eager to uncover the secrets that lie within. With a brisk, yet measured pace which allows key moments of slower characterisation, the film is a satisfying romp through the scandalous convent. Although it never reaches the outrageous extremes of other nunsploitation films such as School of the Holy Beast or Sister Emanuelle, it is still authentically louche and has an intoxicating air of taboo eroticism.

More Film Reviews

Shih Chun is Ho Yun-Qing, an intelligent student who fails his imperial examination and, after failing to find a respectable job well, decides to become a manuscript copyist. His minimal… Suzy Eddie Izzard delivers a masterful performance of duality as the titular character in Doctor Jekyll, Hammer Film Productions’ retelling of The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde,… After Purima Kikaku’s success with their three “Document Porno: Sukeban” films they would move onto a new format for their next attempt at the sukeban genre – the “semi-document”. Whereas… Home invasion films are undoubtedly a lasting source of sporadic dread for moviegoers, with their realism serving to heighten the sense of vulnerability that these scenarios, although made up, evoke…. There is a good reason why Don’t Look Now so rarely feels like it is a horror film. It is much too concerned with going about its daily business as… Door is a 1988 Japanese psychological horror thriller written and directed by Banmei Takahashi with additional writing from Ataru Oikawa. Beginning his career in Pinku Eiga in the 70s, Takahashi…Legend Of The Mountain (1979) Film Review – Triumphant execution of a typical Folktale-ish Narrative

Doctor Jekyll (2023) Review – Well Hello, Ms Hyde…

Semi-Document: Sukeban Bodyguard (1974) Film Review – An Exercise in Grittiness

Clawfoot (2023) Film Review – Who Doesn’t Want a Little Renovation?

Don’t Look Now (1973) Film Retrospective

Door (1988) Film Review – Home Invasion J-Horror [Fantastic Fest]

Hi, I have a borderline obsession with Japanese showa-era culture with much of my free time spent either consuming or researching said culture. Apparently I’m now writing about it as well to share all the useless knowledge I have acquired after countless hours surfing the web and peeling through books and magazines.

![Door (1988) Film Review – Home Invasion J-Horror [Fantastic Fest]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Door-cover-365x180.jpg)