Hello, everybody, this is Anthony and in this article I will explore the ghostly video game series ZERO, a.k.a Fatal Frame in North America a.k.a Project Zero in Europe and Australia. A series most true to the roots of J-Horror. I’ll focus mostly on the first PS2 trilogy here, not the Nintendo entries. Prepare your camera, your spirit radio and your flashlight, and please follow me into the depths of hidden rituals, lost spirits wandering in the darkness of Japanese houses and dark secrets. I know the path…

J-horror wave, the modern and reborn version of Kwaidan eiga, is a transmedia phenomenon that has sneaked its way through novels, mangas, movies, and of course, video game. Games are probably the artistic medias that has the highest potential to make you feel the true terror of Asian horror. This time, you’re not watching passively someone being haunted. You’re haunted. The threat, the ghost, the monster, or whatever makes you shiver with fear, is aiming you and only you.

There are many examples of this ghostly invasion of our consoles and PCs throughout the year. Stand-alone titles like Kuon, The Calling, or the Ju-On video game, but also terrifying franchises that built their mythology through sequels, novelizations, movie adaptations and other media. If there were only two representative example of this, it would be the series Zero, also known as Project Zero or Fatal Frame, and the equally haunting Siren (a.k.a. Forbidden Siren).

Often rightly considered as the most frightening survival horror saga of all time (reputation it sometimes shares however with others, such as Siren, Dead Space, Outlast, of Silent Hill), the Project Zero franchise currently encompasses 5 main games, a spin-off on DS, a 3D tourist attraction in several cities in Japan, novelizations (for the first and second installments), manga series, short stories, a spin-off film adaptation, concerts, and so on. Forget your axes and other shotguns, you cannot kill what’s already dead. You can only hope to seal it away as exorcism, but it will require to face your worst fears and look at it right in the eyes (if your opponents still has eyes, that is). So, arm yourself with a camera and enter if you dare in these desolate traditional Japanese huts where time seems to have stopped and memories float in the dark.

I – The Nightmare Begins – ZERO

“I wonder how long it’s been since my brother and I began to see things other people can’t see.”

The first game is born from the imagination of a certain Makoto Shibata (director) and Keisuke Kikuchi (producer), members of a team of developers of the Tecmo company, later named Project Zero (title that will be used in Europe for the series, therefore). After the development of the Deception franchise, Mr.Shibata and Mr.Kikuchi wanted to create a PS2 game that will be “the scariest experience ever” and explore the darkest corners of fears, but in a very Japanese way, with a story and settings that would mirror Japanese folklore. A folklore that is here more central than in most horror game released so far.

“I think that fear is an emotion that everybody shares. I thought that this might allow more people to enjoy it, and so chose the theme of “fear”. In the past I worked on the Deception series, whose selling point was its dark atmosphere and new game system, but for the time being we had done all we could with that series, so next I wanted to try pushing the theme of fear further, and that’s how it began.” –Mr. Kikuchi

“Japanese houses have things like the shadows of sliding doors, under the floor, attics and the like that have this darkness that seems like something is lurking inside it, right? We made it in a Japanese style because I wanted to show that darkness. […] it seems to me that the emotions of the people who have been there have seeped into these wooden Japanese houses. Meagre happiness, small sentimentalities, terrible memories – all of it. When I immerse myself in that darkness, I feel as though the memories of the deceased are secretly whispering to me. In making this game, we put a lot of attention into creating the rooms so that you could imagine the events of the past from the various remnants lingering there. As you explore the rooms thoroughly, wondering what happened there, I want you to listen out for whispers from the darkness.” –Mr. Shibata

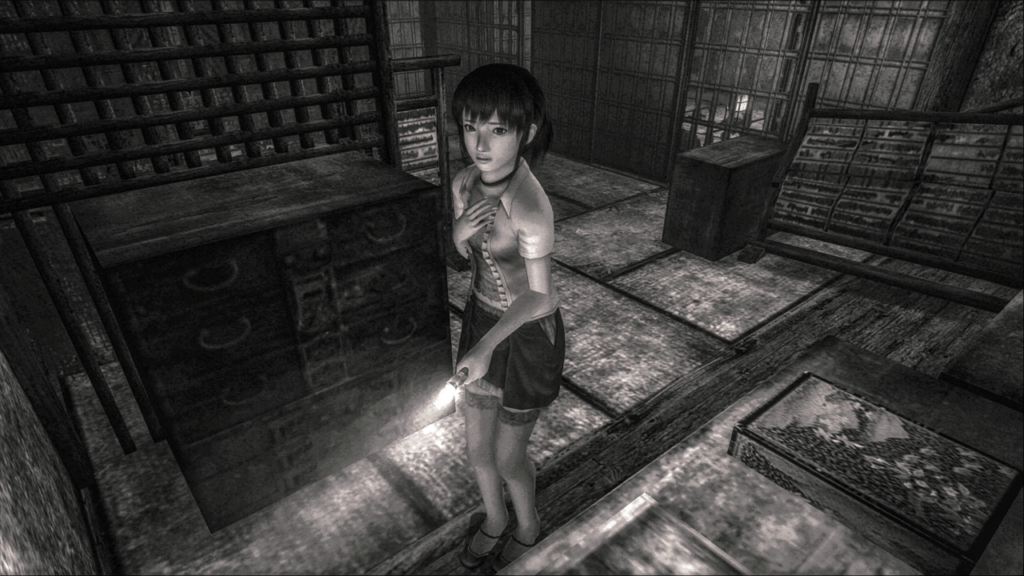

With things like that in mind, and taking inspiration from kwaidan eiga and the modern Ring movie, Zero is a game that embraces Japan, and it is in its country of origin that the game and its sequels will have the most success (unlike a Resident Evil or a Silent Hill, more universal in their themes and using primarily Western inspirations). Hence it is not surprising that the main character is a high school Japanese girl, a very common trope in Japanese scary tales, instead of the more confident and trained protagonists of Resident Evil for instance. However, what is the game about?

The story takes place in 1986. The player controls a young Japanese girl named Miku in search of her brother Mafuyu, a journalist who disappeared in an old abandoned mansion while he was researching his master, a novelist who also disappeared. Armed with his only camera, Miku, trapped in the manor, continues to look for his brother while fighting against the specters in the property. The girl will also have to uncover the secret of the mysterious curse weighing on Himuro Manor and concerning a young girl with a broken heart dressed in a white kimono and dragging ropes.

Your character is vulnerable and scared in the face of paranormal events that threaten her life. An emotional bound is thus created with the player who is all the more afraid that the heroine seems terrified herself – a frail condition. This process will also be a constant in the saga, that of being powerless. The developers removes any notion of traditional combat with a gun or a knife and prefer to focus the game on an immaterial and impalpable threat: the tragic figures and the vengeful ghosts. These yurei are a completely different opponent than mere zombies and deformed monsters. Lost souls, wandering aimlessly in the dark hallways of Himuro Mansion, yelling complaining cries that express their distress in this house full of ugly secrets and dark rituals, their plight mirroring the typical tragic ghosts of J-horror like Sadako, Kayako, or the more ancient Yuki-onna and Tsuchisake-onna.

“As a result, as well as the slow movements of a corpse they also have emotions, a purpose and a personality, and specifying their movements so that a heightening of that emotion translates into attacks.” (Tsuyoshi Iuchi (planner))

For the American release only, the plot is said to be “inspired by real events”, although this statement is very exaggerated: Shibata-san was inspired above all by an urban legend revolving around a real house but it does not go any further, and the ritual depicted in the game is fictitious (the developers tried to imagine the most painful ritual one can think of, which makes the player sympathize with the antagonist), no matter what the American marketers say. If the famous ‘Camera Obscura’, our only way to defeat the spirits, has become the emblematic object of the series, the developers initially planned to make us repel the ghosts with the rays of our flashlight as an idea reminiscent of Alone in the Dark – The New Nightmare. Finally, Shibata-san preferred to opted for the famous camera system, based on a belief that taking pictures of someone “steals” his or her soul. Although the producer Kikushi-san was initially opposed to this idea, proposing traditional Japanese weapons (including Katana, for example). Finally, the director won, and the producer had to admit that he had one of the best ideas for the series.

“When I first heard the idea for the camera, I was opposed to it. If it’s a Japanese horror then you can actively fight back, for example hitting them with a hamaya or writing charms on ofuda talismans, but I thought of cameras as a passive device and couldn’t see how it would mesh with the worldview. As we worked out the details of the proposal, however, I began to see the camera as something that was indispensible to Fatal Frame. Photographs cut out time and space, and I thought that maybe the tension during the moment of a shutter chance might match up with the game system. Not only this, but having to wait for this ghost to draw near and defeat it, even though you don’t want to be anywhere near it, seemed like the most suitable system for stirring up fear. “(Mr. Kikuchi)

“You want to do anything you can to avoid looking directly at scary things like ghosts, right? But I wanted to have a system where they’re scary, but you have no choice but to look at them in order to defeat them, and that’s where the idea to seal them away with a camera came from. “ (Mr. Shibata)

Indeed, the system of capturing spirits by photographing them works on all those levels. Facing your own fears is all the more required as the system leads you to focus on them and waits until they’re near (the closer they are, the better). A relatively long exposure time for a really effective shot. In other word, you have to take great risks to succeed a “fatal frame” or a “zero shot” to cause significant damages to the enemies. On top of that, films (which are basically your ammos) are quite limited. Not to mention you’re dealing with entities that can disappear, teleport behind you before you know it, come through walls, and fly – their animations are vertical in design and not restricted to physics. Each ghost, too, is unique and has a personal story that connects to the events of the game and/or the heroin’s backstory. During your exploration, you learn to know all about it and you feel more and more sorry for those lamenting figures who’re not faceless enemies.

This first entry, sometimes still considered the most frightening game ever created (which was precisely the goal of its creator), forms all the basics of the series: a terrifying, well-worked and obscure atmosphere (with a very haunting soundtrack and beautiful light effects), monochrome visuals, an attention to small details aimed at destabilizing you (42 hauntings can be found), unlikely camera angles, a focus on the exploration and discovery of clues, documents and objects to move forward, some puzzles and doors to unlock as in any game of this type, the mechanism of the camera that will be enriched with new functions afterwards, the traditional wooden-house environments, the ghosts with their own personality and appearance (including non-hostile and helpful ones), the areas to be photographed to reveal clues and create obstacles, and a mysterious plot involving a failed ritual, that reveals itself as you progresses. One more consistent gimmick of the series is worth mentioning: To simulate the heavy and humid atmosphere of Japanese summers (that is strongly connected to the theme of ghosts: wet air is favorable for ghostly apparitions as death is linked with water in Japan), the character’s movements are relatively slow. This goes very well with the slow and dreamy ambiance of the series, and enables the player to take the time to look everywhere and notice items and objects. This aspect, criticized by some, praised by others, will be pushed forward in the sequel, and was made on purpose by Mr.Shibata.

The game leads you to find different types of film more or less effective against ghosts and a point system allows you to improve the efficiency of your only weapon. Points that are obtained not only by exorcising hostile ghosts, but also by quickly capturing non-hostile paranormal activities that often manifest stealthily. The game was also interestingly named Zero which can be pronounced and read as «Rei» (ghost) in Japanese.

“The reason for making the Japanese title “Zero” was because it’s something that should be there but isn’t, or something that shouldn’t be there but is, and it’s nothing and yet something – “zero” is a word that doubtlessly represents ghosts, and it can also be read “rei” (ghost), so I thought it seemed like a perfect fit for a title that deals with spirits. (Mr.Kikuchi)”

A pun will not however cross the borders of the archipelago. Undoubtedly, this name would not have made enough impact with an understandable title. The Pal version of the game remained close to the original title, while the NTSC release completely changed it.This is not the only change between the Eastern and Western versions, however. Several other changes include the appearance of the heroine, Miku, considered too young and who will therefore be aged a few years in the West (she’s no longer in high school but instead university!) and her clothes changed as well. Overall, the game was very well-received worldwide (not as succesful as in Japan, though). For example, in France it came around the same time as Hideo Nakata’s Ring, and each work seemed to have contributed to the other’s success, in this area.

This first Zero game was made with the ambition to create one of the most terrifying games ever made, and it can be said that the goals have been achieved! So achieved that a significant amount of players gave up before finishing it because the game was too scary for them. Something that will lead the development team to rethink their approach in the next entry I will explore in the second part…

“In a word: scary.” – 27/F/Osaka

“The ultimate in scariness is here!” – 17/M/Mie

“You get addicted to the feeling of fear.” – 29/M/Tokyo

“It’s so spooky that I can’t continue.” – 14/F/Tokyo

“It’s actually so scary that I stopped midway through and can’t play any more.” – 26/F/Saitama

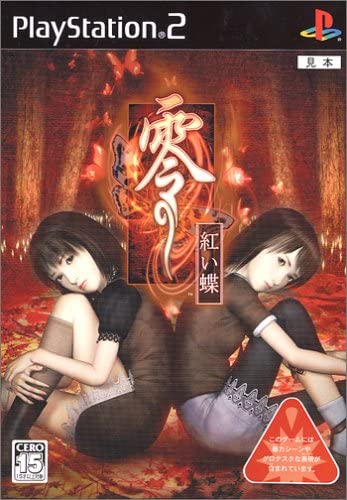

II – Crimson Butterfly – ZERO Akai Chou

“The two chosen children, should be carried to Heaven, on the wings of a butterfly.”

A story of a promise, a story of sacrifices, a story of things that should be together getting separated…the story of ‘Zero Akai Chou’ (a.k.a Project Zero/Fatal Frame II Crimson Butterfly). This sequel is launched and released in 2003, with a more important marketing procedure, including a 3D attraction (called Zero 4D) in several cities like Tokyo and many products such as a short novelization (like the first one), several DVDs, etc. The game, this time, is inspired by legends of isolated haunted villages that make you vanish if you enter them. It reuses and deepens most of the mechanisms and formulas of the previous one, by adding new features to the camera, enlarging the scale (an entire village, obscure, isolated and mysterious, is now to be explored) and by centering the plot on two young twin sisters who are very close since a tragic event of their past. While secretly visiting a place where they used to play as kids, they find themselves trapped in the Minakami village (meaning All Gods’ Village). Time seems to have stopped in an endless night here, and strange rituals involving twins have been performed as a custom.

The two sisters will have to survive in this haunted place while the the main target, and discover their connection to all this. We play as Mio, the youngest twin, who’d do everything to protect her sister Mayu, since an incident that occurred during their childhood for which Mio blames herself. On her behalf, this led Mayu to feel a constant fear of abandonment and a desire to be one with her sister, drawing a parallel with other character’s feelings, and mirroring events of the village’s past…the village where the crimson butterflies dance. A village held forever in the grip of a never-ending night.

This game was made with a higher focus to the narrative and characters, to captivate the players and bring them to play until the end of the adventure despite any fear, in reaction to many fans who didn’t dare finish the first one. The plot is therefore clearer, and arguably better told (the notes are more direct, the cutscenes both scary and beautiful, the atmosphere more «warm»). “Zero Akai Chou isn’t only a scary story”, explained Mr.Shibata, “but also a very sad one as well”.

“Even if people live closely alongside someone else, in the end they will live and die alone. All we can do in a world like this is to make sure that our feelings are the same – in other words, to make promises. What if those promises were to be broken? What if you still went on believing in that promise forever anyway? This is the theme that Fatal Frame II is based upon.” (Mr Shibata)

“The fear that the director requested for Fatal Frame II’s cutscenes had to not just be scary, but be beautiful as well. Since it’s a horror game, by its very it of course nature it has to be scary, but just being scary doesn’t mean just anything will do – ideally, you would be able to feel a subtle Japanese beauty amidst the fear. It’s the kind of issue that could drive someone mad, but we used the movies and images the director showed us as reference, working hard to somehow get closer, bit by bit, to that ideal. CG, sound and story all come together to form the roots of this game, giving it a Fatal Frame-style aesthetic through and through. Please make sure you take the time to properly enjoy this terrifying and beautiful world.”(Mr.Daisuke Inari, CGI movie team)

In the same perspective of keeping the player in front of his screen until the (beautiful) end, the developers have undertaken to tone down the fear a little compared to the first. The game is quieter, more dreamy and less nervous, less cold. However, the result somehow has the opposite effect: the game was considered and is often still considered today as the most frightening entry of the franchise and even the most terrifying game ever made. The atmosphere a little more silent and minimalist is diabolically effective, and the encounters gets the player to face terrifying spirits such as the falling woman, the Kiryu twins or the Kusabi, among others… The ghosts encountered are less grotesque and more ‘human’ in their appearance, but remain intimidating and some are particularly creepy, especially the ones who used to be children and women. One of them is a carbon copy of Sadako in the Ring saga, which almost feels like a “mea culpa” from the developers, admitting Ring as a source of inspiration for the franchise. Others are children playing tag, which is reminiscent of a ghost from the first one.

“Fear that appeals to the imagination is interesting. There are things we couldn’t do because of hardware limitations, as well as things we did do that we can improve on even further in the future, so there’s still a lot of room for investigation. I do think, though, that for now we’ve managed to get a kind of establishment, so please let yourself be terrified by the world, story, and massive scare attraction that we’ve created.” (Jin Hasegawa)

The game takes the opportunity to enrich the combat system via the use of different camera lenses with various effects. Also, this time two other devices enables you to communicate with the spirit world and capture bits of it: a spirit stone radio (with which you can hear the lamenting voices of the victims, or your sister’s voice when she’s missing) and a projector that permits you to watch films that seem to come from the other world. All of these objects have their origin revealed in the third entry. They’re still relevent of one of the main theme of the series, the memories of the past and how they haunted in the present, like ghosts made of bitter feelings, trapped in a prison made of beliefs. Exploring the different houses of Minakami village is stepping on this wounded past that cannot rest. But as twins, you step on it as the main focus of of those tragic figures. The ones that can help them, and they often come to you saying ominous things like “You were born for this purpose” or “The twins of sacrifice have returned”. Menacing phrases that will make more and more sense while you get closer and closer to the end of the path. Crimson Butterfly is a tragedy, after all. A bitter and beautiful piece of macabre poetry, where things like symmetry and promises aren’t just words.

You play an even younger, more slender and seemingly more fragile (and slower) heroin than in the first, but we have to acknowledge the courage with which she confronts the hostile ghosts throughout the adventure. Nothing can stop her from saving her sister, whom you also can play during “telepathic” monochrome stages. In other moments, the sisters are reunited and Mayu slowly follow Mio with her bad foot. A presence that sounds annoying on the paper, but her strong sixth sense makes the ghosts target her as a priority, making her quite useful (and those moments are also a relief in a game in which you spend most of the time alone, facing the darkness on your own). Overall, the game is also simpler with more healing items and films to find, which makes it more playable for the neophyte. The player is supported in their quest until the end, even if he spends the adventure on his or her toes.

Crimson Butterfly also marks the arrival of songwriter/ composer/singer/pop-star Tsuki(ko) Amano who will compose and sing the ending themes of the saga from that date. Her ending song Chou perfectly captured the emotional drama of the game, and plays a big part in what made the conclusion of the story memorable. Up to now, it’s still one of her most praised songs, especially by the fans of the series.

“”Chou”, which was the song I contributed to the first game in the Zero series I worked on, and since not all of my fanbase likes playing games, I definitely wanted to make it a song you didn’t have to have played the game to enjoy. People who haven’t played the game have their “Chou”, and people who have played it have their “Chou” – that was the kind of song I wanted to make. ” (Mrs Amano)

“It’s a really great song. Maybe it wouldn’t be so bad to die if you were listening to this song.” (Mr Shibata)

” Do that once the game’s done, would you? Right now we’re working on the game with all our effort, and making preparations to let you all hear “Chou” as soon as possible. It’s dramatic and beautiful, but also scary. It’s a great fit for this game’s worldview as well, so please look forward to it.” (Mr.Kikuchi)

The game draws its inspiration from multiple media, including detective novels, both Japanese and Western books, the movie The Shining, and most likely the Korean film A Tale of Two Sisters.

“There isn’t any specific story that formed the basis of the game. But the development team studied horror movies and novels from Japan and the West as well as many legends, local traditions, and actual events to extract the most horrific essence of each.” (Mr. Kikuchi)

Its popularity among fans led to a Wii remake that came out after the franchise became owned by Nintendo: Deep Crimson Butterfly. Very close to the original one but with enhanced graphics and a different camera angle, this Wii remake also adds two additional, interesting endings.

“So we started thinking about changing one of the past three games in the Zero series (Zero ~zero~, Akai Chou and Zero ~Shisei no Koe~) to use Tsukihami’s format, and made the proposal to Nintendo right away, but they gave us the counter-proposal, “We will give you the funds to make a new product, not churn things out, so please make it well.” From there we reviewed things, and decided to do a remake based on Akai Chou, the game in the series with an especially high number of fans, and evolve it rather than just make a semi-new game.” (Mr.Kikuchi)

It is also worth mentioning that Crimson Butterfly, originally released on the PS2, had an enhanced Xbox released too, just like the first game. This “Akai Chou 1.5” provides new elements such as one more ending, a full FPS mode, enhanced graphics, etc.

Due to its more varied sets, the visual atmosphere, its beautiful soundtrack and a moving story that touches you deeply, this second Project Zero/Fatal Frame game (or Zero Akai Chou) is a true masterpiece. A perfect horror game and arguably the best survival-horror ever created alongside Silent Hill 2.

After the success of this second entry, the question is, what to do next…

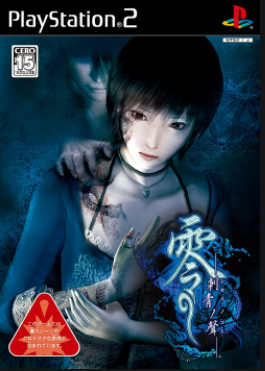

III – The Call of the Tattoo – ZERO Shisei no Koe

“I heard this house was haunted…too bad it’s not.”

Surrounded by a thick veil of mystery, sleep still refuses to give us its terrible secrets. And if the human being always ends up agreeing to dive into this tangle of randomly soothing or tormented dreams, he most often remembers only his worst nightmares. Involved in a sordid story beyond reality, Rei Kurosawa fears more than anything that fateful moment when sleep takes her straight to a restless Hell – because what other name can one give to a place that shelters the resentments of the dead whose souls forever wanders in torment?

After the success of the two first games, the staff of Tecmo immediately started thinking of a third Project Zero adventure in the world of the spirits, that would uncover and gather all the feelings of the previous ones, so as to become the ultimate Zero game, concluding the trilogy. The game is still inspired by Japanese folklore, rituals and legends like the whole series, but this time, fear won’t only lie in mysterious unknown places. It will invade the your everyday life and privacy: your dreams, your home, your body: a fear that would spread. Be warned, this par of the article may contain a few minor spoiler about the plots of the two previous games.

“We had the image colour from the start. Not only falling snow, but also monochrome creating a cold feeling. And then the blue tattoo violating the skin. Something more simply frightening than Zero ~Akai Chou~. A stronger kind of horror.” (–Mr.Shibata)

“The story takes place in two locations: the house where the protagonist, Rei Kurosawa, lives, and a huge, abandoned Japanese house that she visits in her dreams every time she falls asleep. The player is struck by the fear of the writhing presences that dominate the House of Sleep from the darkness, and when they return to the real world, bits and pieces of information about the House of Sleep come to light. Each time they sleep, a tattoo eats away at their body. Miku Hinasaki and Kei Amakura also enter the dream. As the three of them confront their own destinies, you will pursue the manor’s mysteries from their three perspectives. As the player feels like they’re figuring all of this out for themselves, they should also feel themselves being pulled into this world from which they can never go back.” (–Mr.Shibata).

Released in 2005 in Japan, Zero ~Shisei no Koe~ (Voice of the Tatoo) or Project Zero/Fatal Frame 3 The Tormented in the West, tells the story of an adult woman who happens to be a freelance photographer (re-using a skipped idea of the first game) who lost her fiancee, Yuu Asou, in a car crash caused by her careless driving. Trying to uncover from sadness and a bitter survivor’s guilt, she gets sight of him as she takes photos of an abandoned manor. This is the beginning of a long nightmare.

This time, the main character is a full grown-up person and not much is known about her childhood. Zero 3 is a tragedy that comes in adulthood as the producer explains:

“We wanted to make the protagonist someone with a degree of life experience, at an age where she could take that pain. If she were too young it would simply end at sadness being sad, pain being pain. We wanted her to be an adult who, despite losing a person dear to her in the opening, lives on while shouldering that regret, grief and suffering.” (–Mr.Kikuchi)

Similarly to Silent Hill 4 The Room, the game makes you shift from a dreamworld to the real world and the latter feels only safe at first. As the story unfolds and secrets are discovered, even your home isn’t a safe place anymore. The emotional connection to the protagonists is strengthened as you get to know Rei’s place and personality, as well as her relationship with Miku, her assistant and the protagonist of the first game, also confronted with similar feelings and dilemmas as Rei. One of the key theme of the game is the loss of a relative after surviving a tragedy. This is something the three protagonists of the Zero trilogy have in common, making them martyrs of their own respective adventures (a sacrifice is always required to save the day) and linking them together. This time, though, the loss occurs as the beginning of the story, therefore taking a different pattern than before. The third playable characters was originally planned to be Mio, the surviving twin of Crimson Buttefly. Her, Miku and Rei were even supposed to live all three in the same house. Yet, the creators explain why they changed their minds:

“At first, Mio was the third protagonist. But their story from Akai Chou was mostly complete, the story too strong. That’s when their uncle, Kei, became a protagonist.” (Mr.Kikuchi)

“With regards to Akai Chou, it’s all been said already. We would’ve had to have to have put all of those elements in there. And if we had, the scenario would’ve bloated to more than double the size and be consumed by Akai Chou. To that extent, since that story was so powerful, we had Mio appear in a manner than wouldn’t conflict with the story of Akai Chou.” (–Mr.Shibata)

Having three protagonists also allowed to expend the gameplay, giving them specific abilities (hiding, slow the time down, etc) as they face the ghosts of the manor. Besides that, the gameplay is overall similar to the previous ones, with different lenses like in Crimson Buttefly and only a few additions. The map is probably the widest and most labyrinth-like of the trilogy. The dreamworld can be seen as a mix of locations of the first two games (Himuro Mansion and All Gods’ village) alongside the main, original one, a dream representation of the Kuze Shrine visited by Rei in the intro. This aspect pleased a part of the players who enjoyed the exploration of a more extensive map and being lost in the mysterious location. Others, however, didn’t enjoy much wandering in such a vast place, having difficulties to figure out where to go or where which door for the key they just found. Either way, one can’t deny the Manor of Sleep is a place full of hauntings and truly spooky moments. New freaky ghosts are encountered, such as a mysterious stalking tattooed topless woman, four Handmaidens who wouldn’t mind driving a stick on your limbs, as well some familiar figures from the first two games…

Among the new things, most players remember the miasma, a monochrome dimension where you become an easy target for the tattooed ghost, and from which you can escape using candles (another arguable similarity with Silent Hill 4 in which holy candles are used to exorcise hauntings). These phases keep you in a constant fear of running out of time and being stuck again into this unpleasant hellish state. Once awake, you can barely feel safe due to the strange phenomenon that can occur in the house, giving a more realistic aspect to the game. The paranormal activities occurring now in a modern world (and not in an old Japanese house) remind a lot of J-horror movies like Ju-On or Dark Water.

“In the past in the series, the ending has always finished with “becoming zero”. This game will grip you. The story begins with the protagonist in the worst situation, and you really have to see how things come to their conclusion at the end. Besides this, we’ve prepared all kinds of things you wouldn’t want to happen in reality to your own house so you can feel the fear of everyday things and abnormality.” (–Mr.Kikuchi)

Yet another specificity of The Tormented is how much the game focuses on the documentation and an active job of investigation and researches is now demanded to the player, in order to find out the hows and whys. Letters sent by Kei, notes found in the real world on in dreams, audio tapes, photographs taken in your sleep then developed in your labo, all of these are clues to discover the secrets of the Kuze Shrine: why the spreading tattoo? What is this strange lullaby sung in an ancient dialect? What happened to the “spirited away” persons Rei encounters in her dreams? Why does she see her boyfriend in dreams? Who’s this mysterious tattooed girl? To get all these answers, Rei can give her findings to Miku who would investigate on her own and then reports the result of her researches. She also has to plunge into the discoveries that Kei and Yuu had done before his disappearance. Once again, Zero drives you into the mystic world of Japanese legends and keeps you interested until the end. Some players didn’t like this aspect, pointing out the game has too much readings (especially compared to the second one who was more straight and easily understandable without too much investigation). Of course, one cannot satisfy everybody, but fortunately Rei writes down everything she learns in her notebook as the story progresses.

“With the first game we created a scary environment, and with the second game we created a scary and sad world and story. For this game, we focused our attention on the game system during development. […]We used a fantastical scariness in the last game, so in Shisei no Koe we leaned towards a clearer, easier to understand fear.” (Mr.Kikuchi)

The game provides a very realistic portrait of characters saddened by the loss of someone, which is shown through the details given to it. For instance, Rei can’t bring herself to throw her lover’s belongings away, Miku is still haunted by the memory of her brother who was the whole Earth and Heaven for her, and can’t forgive herself for having escaped. Ultimately, not only do we feel sorry for the characters, but we also relate to their doubts, grief, and weaknesses. We fear they would themselves be carried away as they slowly sink into exhaustment, but we can’t help wondering, “Would I do the same? Can pages stay turned forever?”.

The art direction is still as important in this third game as in the previous ones (something the series is known to value a lot). Great visuals include the peaceful snow falling in the manor, monochrome sequences of obscure rituals, creative shrines and altars. The sound still plays a major role in the ambiance: voices are heard during the pause menu, an eerie sound follow you everywhere while you explore the locations, and the lamenting ghost voices make you shiver. All of these ingredients are the perfect recipe for a true horror game that would haunt you after you finish it.

“I think that there’s something like a formula for scariness. […] Also, sound is of course the lifeblood of a horror game, so we paid attention to things like faint whispers and footsteps. Feeling presences and bringing out the atmosphere is tied to making you imagine the fear. […] I think isolation is the scariest. Isolation stops you from connecting with other people, and I think that in the end even dying is lonely.” (–Mr.Kikuchi)

For the ending song, Tsuki Amano comes back to compose the song “Koe” (voice) a powerful piece that summarizes and enriches the themes of the game as the creators explains:

“This is her own interpretation of the game’s theme, and if you compare the “voice” told at the end of the game and Tsukiko’s “voice” (“Koe”), I think you will find an even deeper message. “ (–Mr.Shibata)

“”Koe” take on the same theme and the same goal but with different approaches. In my eyes, both are correct. When you add them together, they become a perfect “Zero”. I can’t reveal the details of the ending here, of course, but I hope to someday, somewhere be able to talk about it in depth.” (–Mr.Kikuchi)

Unlike the two previous ones, this game doesn’t have a novelization, but instead a comic anthology was released, featuring 7 serious stories and 3 parody ones. As their “ultimate PS2 game”, Shisei no Koe won’t have an Xbox port as the creators thought the game didn’t need an upgraded version. The visuals were already satisfying, and they didn’t feel another ending was required. They also didn’t know what would be the future of the series, but had a few ideas.

“ For now, the story is over. But since each game is its own story, there will be other episodes made in the Zero series. Well, at the present time we don’t have anything really planned. Of course, if we can make something new, we’d like to do more. Maybe if Shibata has another dream […] it might be nice to make the best of Zero to create a completely different kind of game. We might look for something completely new, not binding the series to a genre or console. I think that’s what the players would want. In the end, it’s only the story of Zero until now that’s complete, which doesn’t mean the end of the Zero world. I think the time when we can give you a new Zero will definitely come, so please wait until then.” (–Mr.Kikuchi)

In the end, it was not the final of Zero world, but the following will indeed mark a change in the franchise while keeping it attached to the survival horror genre. The series was sold to Nintendo and the collaboration with Tecmo would lead to Mask of the Lunear Eclipse as the fourth entry. This would be followed by spin-off on 3DS (called Spirit Camera), a remake of the second entry (Deep Crimson Butterfly), and a 5th entry named Maiden of Black Waters for the WiiU.

IV – A Curse Affecting Only Girls – The Movie

While Christophe Gans (director of the Silent Hill movie) confirmed in several interviews he’s working on a new Project Zero movie, let’s not forget the series already had a movie adaptation, released in Japan in 2014.

Gekijô-ban Zero, directed by Mari Azato and based on the novel Rei – Zero – Onnanoko Dake Ga Kakaru Noroi (aka Fatal Frame – A curse that affects only girls) by Eiji Ōtsuka is a movie that devises fans. Some people call it an unfaithful outrage, because there’s “no battles with ghosts, wtf” and wonder “where is the camera obscura”, while others praise it as a truly good, well made adaptation that does the series justice. I’m among the later and tend to defend the movie.

The movie is actually pretty faithful of the Fatal Frame series and in the most unexpected, and yet the best way: it is close to it on the depth of it, not on the surface like a lot of mindless adaptations are (but isn’t it what a many fans demand, actually?). Though it is a modernized version of it, we find the common tropes of the series, reinterpreted in another context (failed ritual in the past and its consequences in the future, the need to put a resolution to it to stop being tormented, the impossibility of running away from what’s been done in the past, broken promises etc). This recontextualization adds diversity to the franchise and expends it. But above all, it reaches (or at least, tries hard to get near) the emotional impact of the games. That’s the major point. I’ve felt moved watching it, in a similar way than when I was playing the original games. Because they’re not only scary games, but also heartbreaking ones with very sad story. That’s one of their main quality and what made me fan of them, and I found it in the movie.

And to me this is way more precious than an adaptation that is only faithful in a superficial level, missing the true substance, just for fan service. Because anybody could make a movie adaptations with the gimmicks and gameplay mechanics but missing the depth (I mean, SH Revelation 3D does have a flashlight, fog, darkness, creepy nurses…and is it a good adaptation?). That is to say, a movie focused on gameplay tropes like the Camera Obscura, ghost battles, etc. And yes, “gameplay” tropes. The camera and combat system are among the things that made Project Zero unique…as a game. But games and movies are separate media, with their own specificity, and copy/paste one to transpose the other is rarely a good idea. This system with the camera works as a game, but it would barely fit a movie, you don’t play a movie, you watch it passively and that’s how it reaches you, emotionally. That’s how this movie wins, in my opinion.

So I’m glad we had a movie that focused on the depth and themes of the games, rather than a soulless adaptation that features all the aspects of the game just for fan service. The fascinating use of photos and what it can symbolizes in a ghost story are there, but used differently than in the game, cause we’re not in the game. And the series is rich enough to explore different settings, different times, and different media with diversity as long as it keeps the roots of it. In my view, that’s how this adaptation succeeded. Adaptation has a different meaning than transcription. And faithfulness shouldn’t be a matter of look, or all we’ll get is a shell without a ghost. An empty shell. I accept the changes from a medium to another, especially if the works still makes me feel the same (or remind me of how an original work made me feel). And yes, I must admit I almost shed a tear the first time I’ve seen the movie…just like when finishing the games.

As an adaptation of the novel, and not directly from a specific game, I think it must be seen as a spin-off anyway. An alternate Zero sorry. But a very nice one as far as I’m concerned. It’s also a surprisingly “soft” (dare I say, warm) J-horror movie, with quite a poetic atmosphere and not brutal scares. And “warm” is an adjective I actually often use when describing some aspects of the games, even if I regard it as the scariest game series along with Forbidden Siren.

Obviously, I stepped away from the neutral tone of the article here to describe what’s only my opinion and I perfectly understand that other people didn’t like the movie, or didn’t find what they hoped to see in a Fatal Frame/Project Zero movie. There are other fanmade movies that are not only well done, but also directly closer to the games I wouldn’t mind an adaptation that is more obviously and directly close to the games, hopefully we’ll see that. In the meantime, I’m very grateful of the work that has been made on this movie. In the end, I consider this Fatal Frame movie to be one of the best (if not the best) movie adaptation of a horror game franchise so far, along with the Forbidden Siren one and the first Silent Hill movie.

This is the end of the journey for tonight. I hope you didn’t lose yourself among the freaky spirits nor did you drop your camera obscura. I also hope you enjoyed the ride and it paid a fair homage to this beautiful art piece of Japanese horror.

More Video Game Reviews:

Zero: Tsukihami no Kamen [零〜月蝕の仮面〜], or Zero: Mask of the Lunar Eclipse, was the fourth main entry in the Zero series and a switch from Sony’s platform to Nintendo’s. For the… Gregory Horror Show is a 2003 Japanese mystery survival horror, developed by Capcom and released on PS2 in Japan and in Europe a few months later. The game is based… Several years ago, a small Japanese third-person horror game known as GOHOME started to make waves in the Let’s Play YouTube community. Created by the VTuber known as Itimatu Ichimatsu… With a retro approach to rudimentary mechanics, and grim pixelated presentation, World of Horror is a passionate tribute to J-Horror; notably towards the eminent horror mangaka ‘Junji Ito’ who specializes… Atlus’s Persona series is a critically acclaimed video game franchise which depicts a group of high-school students battling creatures known as Shadows by using “Personas.” Personas in this context are… You may already be aware of the hit mobile game Fate/Grand Order, which has a really fun mix of anime, historical figures, folklore, waifus and even some sci-fi elements! Right…Fatal Frame IV: Mask of the Lunar Eclipse Review

Gregory Horror Show (2003) Game Review – Strange Survival-Horror

GOHOME (2020) Game Review – Homeward Bound

WORLD OF HORROR: An Investigative Interactive RPG of Junji Ito and Lovecraft’s dreams

Persona 3 The Movie #2 : Midsummer Knight’s Dream (2014) Review – Battlefield Unconscious

Japanese Folklore of Fate/Grand Order: The Tongue-Cut Sparrow

Student and former short film maker, Anthony Auzy always loved scary stories and horror content, with a special fondness for Asian horror. It inspires him for poem books, short stories, short films and videos, and other creations. He like to dig hidden findings that may be overlooked or unnoticed, and I enjoy scary Asian games and spooky reads. Besides watching many J-horror movies, he keens on exploring how the movement was born and expanded in different forms of media, and study its cultural impact.