It is safe to say that the global coronavirus pandemic has drastically changed our world and the way we both operate and interact within it. Nowhere has this been more overwhelmingly true than in the film industry. What started with horror fans celebrating their favorite on-brand pandemic themed features has slowly devolved into a mired swamp of delayed productions and an all too unfortunate amount of questions with regards to the future of movie theaters.

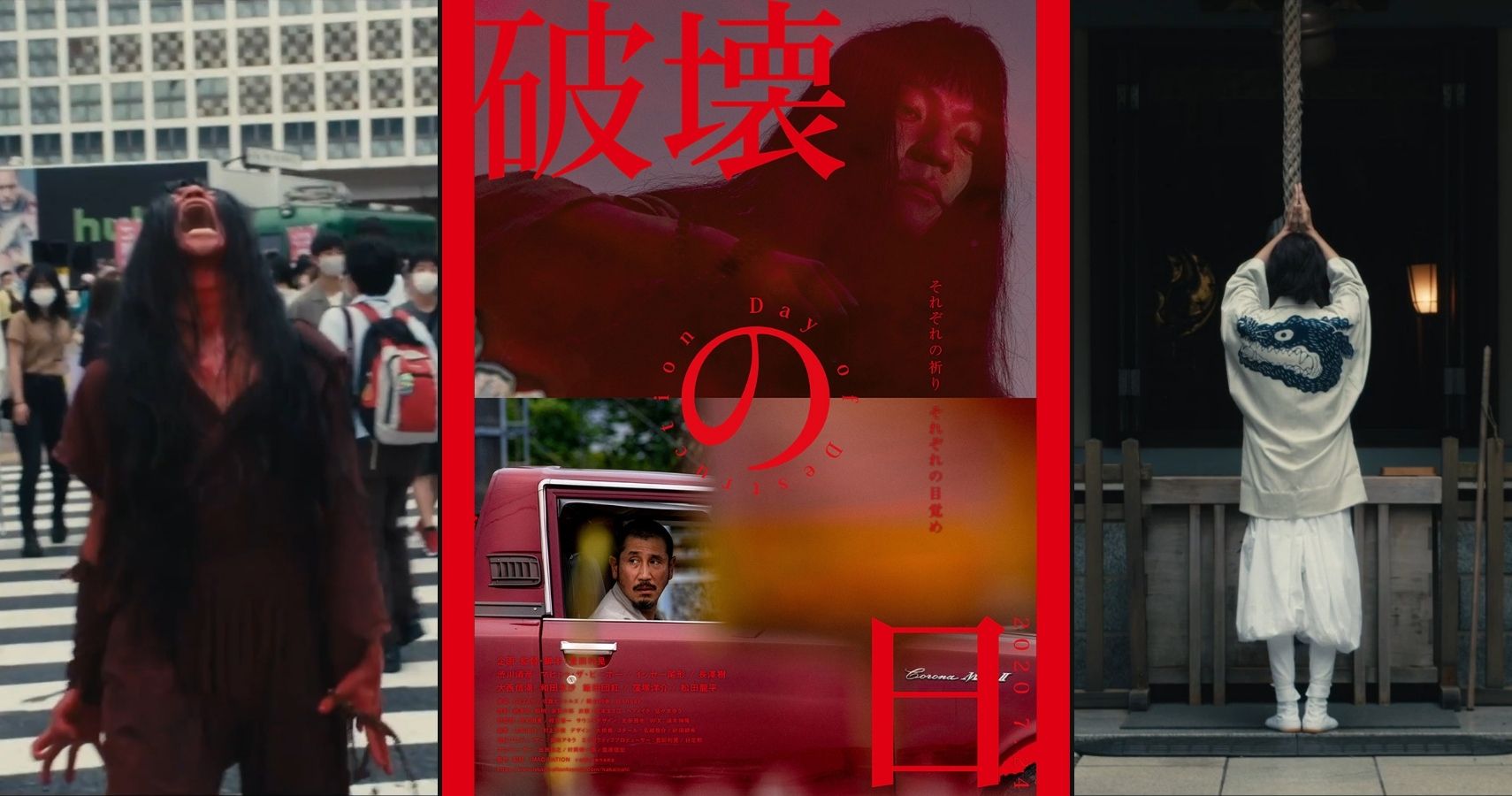

Yet there have been those directors that have risen to the challenge taking on all the many restrictions and considerations to work their craft among the COVID-19 crisis and create some truly interesting pieces of cinema. From Rob Savage’s Zoom-based supernatural found footage darling Host to Shinichiro Ueda drawing up the same creative energy from One Cut of the Dead to craft its Mission: Remote spin-off, horror fans have been blessed with an embarrassment of riches despite it all. However, while the aforementioned films simply tackle the problem of filmmaking amid COVID-19, Toshiaki Toyoda’s The Day of Destruction cuts viewers to their core as it tackles not only the pandemic itself, but how we collectively have handled things. Clocking in at just under an hour, it serves as a concentrated dose of impactful filmmaking.

The movie premiered July 24th 2020, which would have originally been the opening day of the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games before its postponement. With an initial premise to tackle the greed of the specter of capitalism and its hold over the city, as production became troubled due to the state of emergency declared in response to the widespread outbreak of COVID-19 the scenario was revised giving it an even more timely scope. Filmed in only eight days, the production managed to push its efforts to still hit the intended release date despite the many delays and complications delivering to viewers an intense and haunting film. This is not a conventional horror film packed with jump scares, but a dread filled gaze at the world around us.

Toyoda, as a director, is no stranger to such intensity either. With early efforts like the youth dramas Pornostar and Blue Spring, Toyoda has exhibited a wild punk rock aesthetic overwhelming the viewer for each film to make its point clear. While you can see a level of maturity in the craft within his filmography going forward, The Day of Destruction marks a return to that same angry punk rock energy hammering its point across to anyone it can take hold of.

The film is gorgeously shot, and this immediately places it into a different category from many of the other pandemic-made flicks which have relied on a found footage style presentation. We open in black and white with businessman Shinno (played by Ryuhei Matsuda) wandering through a seemingly abandoned town coming to a deserted mine. Here he meets with and bribes one of the former employees, Teppei (played by Kiyohiko Shibukawa), to be let in and see the “monster” that everyone has been talking about and that has presumably caused operations to shut down. Through slow atmospheric tracking shots we see Shinno press deeper within the mine all the while allowing a lot of tension and dread to build as viewers are left to ponder exactly what sort of creature resides within. This drags just the perfect length to place you on edge waiting for the moment to come.

When we finally see the monster, it is far from conventional. This is no traditional movie monster or guy in a rubber suit. Awaiting Shinno is a quivering pulsing horde of fleshy mass. If this creature is meant to be a sort of embodiment of the pandemic plaguing the world today, then it comes in no form where it can be engaged with or handled. Instead, it thrives in the realm of the unknown like the embodiment of the eldritch entities Lovecraft wrote of in his Cthulhu Mythos smashed up with the unnerving creations found in the body horror flicks of David Cronenberg. Shinno can only remark that, “One hell of a monstrosity has been born.”

The rest of the film is washed in vibrant color and we transition to the primary story with a powerful song about the pandemic set to the credits and scenes of iconic relevant landmarks like the Tokyo Olympic stadium (which stands as an embodiment of the greed Toyoda originally set out to criticize) and the Diamond Princess cruise ship (famously locked down in quarantine during the early days of the pandemic). The lyrics seem as much a part of the narrative as anything else venting frustration against the restrictions brought about by the pandemic while also questioning our humanity and the way people can so easily turn against one another despite being in a time when we need to pull together. Like a thesis statement for the entire film, the singer challenges us to shout out and prove whether we are still alive.

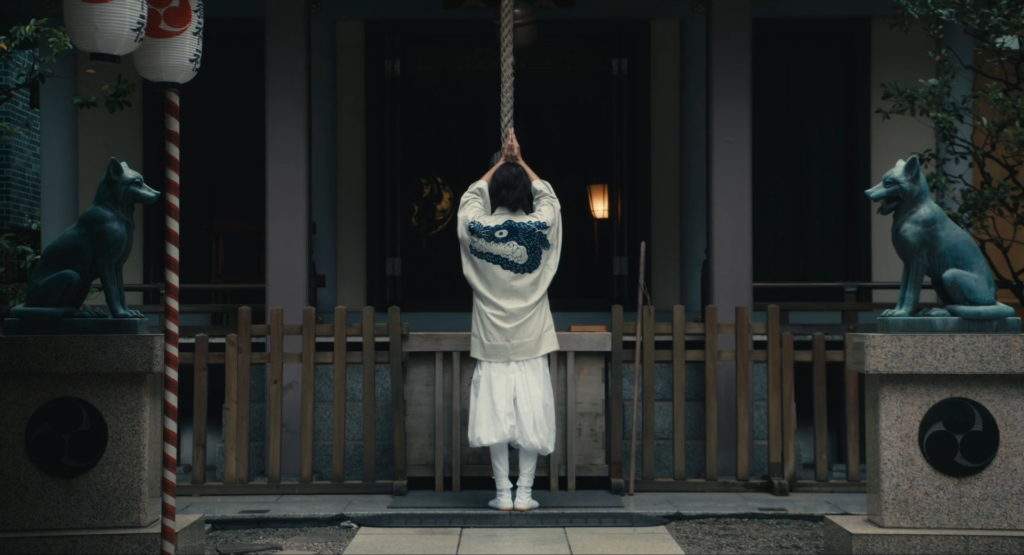

The meat of the narrative follows Teppei, who since the prologue has spent some time training as a monk and now works as a mechanic, and his friend and fellow ascetic Kenichi (who is expertly played by musician MahiTo The People of the band Gezan letting his vocal talents shine with some amazing screams). We learn that from the monster discovered in the opening a great plague has spread forth. While we’re never given clear details on the nature of this plague, it clearly functions as a parallel to the coronavirus. Teppei, Kenichi and the other ascetics of the Mount Resurrection-Wolf shrine have been hoping through prayer to bring about the end of the epidemic. We get a curious and, for those with a fear of being buried alive, difficult scene of Kenichi attempting self-mummification in sacrifice to stop the plague.

As things progress we bounce between the current story and some time before as we learn more about these two monks, their relationships, and that Kenichi’s fervor in stopping the plague rests on wanting to save his younger sister who has been suffering since the onset of the epidemic. We also get some surreal scenes of everyday people going crazy with a businessman raging in a field about how everyone is infected and life is over, a woman shouting in the streets about how those who die from the plague will get discarded like trash, and even a man violently banging at the doors of a sealed building accusing those inside of being politicians and wealthy elite sealing themselves away safely while abandoning everyone else outside to suffer.

With a focus on asceticism, the film delves into some pretty heavy religious themes and I would not begin to consider myself qualified or the right person to break all this down. From the prophecy of the arrival of Maitreiya in Buddhist tradition to the idea of Genriki as supernatural powers acquired through devout spiritual practice. The film offers a buffet of interesting ideas to chase down and learn more about, but for the casual viewer the core message shines through regardless of your level of familiarity: prayer alone will not stop the monster. Jiro (played by Issei Ogata), another monk prominently featured throughout, explains clearly to Kenichi stating, “You can’t destroy something intangible.” This fact goes just as true for a plague as it does for the evils we subject one another to.

The climax of the film sees Kenichi falling to his own rage and despair becoming possessed by a demon and heading off to Tokyo to unleash his anger. Meanwhile, Teppei prepares to try and free him from its influence. This section of the film brings one of the most powerful moments in the story as we are shown Kenichi bathed in red wandering through a crowded crosswalk in Tokyo howling and shouting at the top of his lungs. In these moments he truly seems otherworldly, giving a wild convulsing performance that channels the same haunting inhuman energy portrayed by Isabelle Adjani during the infamous subway scene of Andrzej Zulawski’s Possession.

The ending is somewhat inconclusive, not unlike our current situation, but we’re left with a message of hope. We cannot destroy the monster, the plague, for as Jiro states in the film it is simply a part of nature that has to be guided through to its proper path. Instead, what needs to be faced is our own demons: the greed, hate, and despair that can so easily weigh anyone down and in turn makes us selfish and blind to the suffering of others and the world around us. All that can only begin by taking a first step with the intention to want to change things, for ourselves and for the world. With such a powerful message, haunting tone, killer soundtrack, and a pointed look at life during a pandemic, for me The Day of Destruction should be considered near required viewing for everyone.

The message isn’t subtle throughout the film, but that is Toyoda’s punk rock aesthetic shining through. These aren’t small ideas wrapped in subtle metaphor, but a madman in the streets wielding a megaphone crying out for anyone that is willing to listen and understand. This is the sort of transgressive in your face high-energy impactful filmmaking that I love which is equally exemplified in many other Japanese directors’ works ranging from Shinya Tsukamoto to Takeshi Miike and Sion Sono. Despite this, I never found The Day of Destruction to be overly preachy in any way. It doesn’t command a solution for us to follow, instead merely pointing out issues and entreating us to pay attention and do something about it.

Viewers are left to decide for themselves what that something is, but The Day of Destruction is a strong affecting wail of a movie begging us to notice the world around us and take action to make it a better place before it is too late.

More Film Reviews:

I’ve Died A Lot Lately (2022) Film Review – Death and Rebirth of a Slacker

Having recently lost her grandmother, Satoko Sato finds herself deeply withdrawn from the pressures of Covid landing her in the position of a NEET. However, at the age of 32,…

Suicide Forest Village (2021) Film Review – Shimizu Has Such Sights to Show You

I distinctly remember when it was announced that Takashi Shimizu, one of the most consistent contributors to Japanese horror over the last two decades, was going to direct a film…

The Toll (2020) Team Review – Whispers of Violence and Despair

When Cami orders a taxi service to take her to her father’s country home, she’s hoping for a quiet and uneventful ride. But a wrong turn by Spencer, her chatty…

Dagr (2024) Film Review – Found Footage Folk Horror That Slaps

Dagr (2024), by director Matthew Butler-Hart and produced by Fizz & Ginger Films, is the perfect found footage film: a labour of love from a small but incredibly talented creative…

Sweet Home (2020) Series Review: Horror, Tragedy and Monsters

Sweet Home, a South Korean horror TV show based on a webtoon of the same name, is a story about an epidemic that causes humans to transform into horrific monsters,…

It (2017) Film Review – Reboot of a Stephen King Classic

The film It (2017) surprised me. In fact, I saw it five times due to how much I enjoyed it! Unlike a majority of modern horror films, it focused more…

Dustin is a potentially overqualified office worker who has a lifelong love and fascination with Japan and all things Horror. With a bachelor’s in English Literature and a master’s in Library Science, he devotes way too much time to researching and thinking critically about the media he enjoys. When not celebrating trashy horror films, anime, and idol music, he can be found raving about all things genre cinema as a co-host on Genre Exposure: A Film Podcast or indulging a passion for storytelling through tabletop roleplaying games.