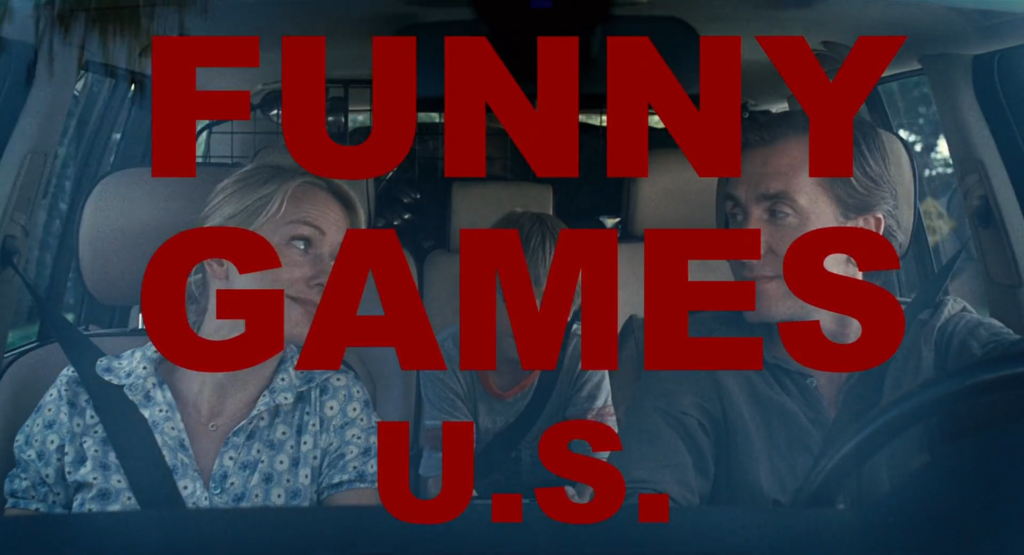

Funny Games begins with an idealised, upper-middle-class family, driving through lush green woodland, beside sun-baked lakes, and playing “guess the classical composer” on the car’s audio system. The mild serenity of Handel and Mozart is then smashed by the movie’s title, appearing in huge red letters across the screen, accompanied by the most stygian piece of music I have ever heard. The film sets its stall out early, broadcasting its intent to subvert onscreen niceties and viscerally engage the audience. The opening title track, “Bonehead”, is by an experimental avant-garde project called Naked City, headed by saxophonist Frank Zorn, who attempted to test the very limits of composition and improvisation. Such abrasive musical choices are perfectly in keeping with a film whose main aim is to alienate the intended audience and cause them to question their expectations.

This 2007 production is a shot-for-shot remake of writer/director Michael Haneke’s Austrian original, made a decade earlier. Unlike Gus Van Sant’s pointless 1998 remake of Psycho, this film exists to enable the wider accessibility that its change in language would allow.

In this offering, the outwardly perfect suburban poster family are played by Tim Roth, Naomi Watts and Devon Gearhart, with their well-mannered assailants portrayed by Michael Pitt and Brady Corbet. Pitt, at the time, was most recognisable from his stint on 90’s teen drama Dawson’s Creek and the film The Dreamers, making his character’s actions in this movie stand out in contrast.

Ostensibly a home invasion film, Funny Games follows the familial trio as they arrive at their gated holiday home before going on to meet Peter and Paul, the two “little birdies” who ingratiate themselves into their home only to callously brutalise, torture, and torment the entire family over the course of the evening. On the face of it Funny Games could be considered as just another schlocky addition to the vulgarly sadistic torture porn genre. Slowly at first, however, Haneke reveals a far more ingenious adaptation that challenges the audience’s preconceived ideas by distorting both the concept of a character’s self-awareness and what constitutes viewers’ entertainment.

The growing tension is well handled as the film’s tormentors are introduced and the viewers’ expectations (knowing more than the unwitting, soon-to-be victims) are leaned upon to ratchet up the dread, safe in the certainty that a nightmare ordeal is imminent for the naïve family at the film’s centre.

The preppy, clean-cut antagonists carry with them an unnerving strangeness, not just due to their gradually revealed sadistic psychopathy, but by their increasing ability to break the fourth wall. What starts out as knowing looking down at the camera, quickly becomes Paul asking direct questions of the audience, and then, to thwart Ann’s escape, he displays the ability to rewind the movie itself, to save his companion and maintain control over the family. Both Peter and Paul know they are in a film and as such represent the viewer and the violent whims and expectations of the modern horror audience. To them, the whole film, and the atrocities they inflict, are the “Funny Games” of the movie’s title; like players of a realistic computer game entertaining themselves by torturing NPCs (non-player characters), or viewers of horror films finding amusement in dramatised suffering.

The aptly named Peter and Paul are never at risk, like the audience, their presence is only ever temporary, they can fly away, avoiding any justice, whenever they cease to be entertained. Their well-mannered, middle-class entitlement, and safety from the repercussions of their despicable actions, bring with it current day concerns with privilege and connotations of real-life issues such as the trial of Brock Allen Turner in 2016, and its perceived limited punitive outcomes.

In many ways, the abasement of the family can be seen to be carried out by the product of bourgeois entitlement, and aspects of Marxist alienation from human nature. Peter and Paul are both portrayed as college-aged, country club-styled, white elites whose cold detachment, and gleeful dehumanising of those considered beneath them, mirror the theorised symptoms of having achieved the higher levels of social stratification, as obtained by the successful, affluent upbringing it can be assumed they both enjoyed. They could easily be the product of a family much like the ones they terrorise. Likewise, might George and Ann’s son have grown into a similarly amoral young man? If not a psychopathic killer, someone who’s as entertained by staged torture as Peter and Paul, or as the viewer?

By making the two characters cognisant of the media in which they exist, and in control of the film itself, Haneke successfully aligns the viewer with the two protagonists, making us complicit with their choice of “entertainment”.

The film goes further in alienating the audience and forces us to reflect on what exactly it is we want from the film, and what we expect to receive. Throughout the film Haneke pans away from climactic violence, denying the viewer the voyeuristic pleasure of witnessing a murder or prolonged acts of violence. He, instead, chooses to linger on clumsy, un-dramatic shots of Ann, bound and struggling to stay upright, as well as making her final demise, the killing of the film’s possible final girl, a swift, unsatisfying shove overboard. This purposefully gives the audience what they don’t want, and, by doing so, makes them question why they feel denied. Are we disappointed we couldn’t see the brutal stabbing of the emasculated patriarch, or feel deprived of a more violent finale in the killing of Ann?

Taking such creative liberties with metaphysics, and audience alienation, pushes Funny Games into more arthouse, even philosophic, territory, allowing it to stand a clear head and shoulders above less cerebral home invasion/torture horrors that clogged up the noughties as a backlash against the glossy ’90s.

The highbrow concepts, skilled directing, high production values, and quality acting would make it, if released today, mentioned in the same breath as works by Ari Aster or Jordan Peele. It would, I believe, be similarly mislabelled as “Elevated Horror”; a modern term that undermines the genre with its elitist undertones. Like “Psychological Thriller”, it offers critics a respectable shield when forced to praise the lowliest of genre cinema. It’s interesting to note that Funny Games, like The Silence of the Lambs (1991), is categorised on IMDB as Crime/Drama/Thriller, with no “horror” label in sight.

The fact this film could be grouped with such contemporary works is, even more, an impressive feat if you consider it to be, technically, an example of the oft-derided, commonly misfiring, class of film: a remake.