Co-Author Lisa Lebel

Diana Toucedo’s Thirty Souls casts a gaze on an isolated, slowly dissolving community in Galicia where “life doesn’t end, but rather becomes something else.” This is due in part to possible supernatural forces at work and also because the dead really seem to share the same space as the living – memory works a little differently over here. The film, which fits quite comfortably under the “existential horror” umbrella, accompanies the inhabitants of O Courel throughout their daily lives and also showcases their rather unique attitude towards death. Thirty Souls is a rare docufiction that not only leaves the viewer pondering the multitude of ideas it displays, but which can also make one very keen on visiting the rural mountain land where its story takes place. Because of its potent blend of anthropological observations, magical realism and a mystery-horror element that becomes more pronounced in its final fifteen minutes, Thirty Souls might have viewers planning on retracing the protagonist Alba’s steps, in the same way that people can now enroll as Hogwarts students or visit The DaVinci Code locations across multiple countries.

For those unfamiliar with the term, docufiction is the cinematic combination of a film shot in a documentary style and fictional elements, in an attempt to capture reality and truth by means of artistic expression instead of a simple chronicling of events. Used mostly by experimental filmmakers, it is not to be confused with mockumentaries or docudramas, but sometimes overlaps with the field of visual anthropology. Docufictions essentially feature non-actors (nonprofessional, untrained actors) playing themselves, with a fictional scenario created to heighten the distinctive features of the setting or characters and are often filmed in real time.

Thirty Souls paints a slow, lyrical, contemplative portrait of life in O Courel, with sweeping landscape shots, freezing snow and bubbling brooks occupying the same amount of space as a macabre mystery plot surrounding the disappearance of a young girl who can see dead people. It simply tries to capture the imperceptible, the blurred lines between life and death, with simple but effective means – the sounds of nature and its breathtaking vistas, dramatic monologues, a script filled with great insights, but above all – masterful, intuitive camerawork. It feels like a breath of fresh air, managing to fully immerse the viewer in a strange, but very real world, and then shaking that foundation and trust with some truly terrifying surreal scenes. Its contemplative moments will be a test of patience for some, but they make a lot of sense in retrospect and help the movie stand out: they viewers become the camera placed on the shoulders of the weary inhabitants of the village, and they travel where the young protagonist travels (she is the only character in the movie who displays any agency – the others are fixed in place, happy to recount and remember).

Thirty Souls is possibly one of the best movies about death ever made, and for those interested in the macabre or folk tales, it is certain to be an extremely rewarding watch. Instead of focusing on the terror (like many modern horror movies) this film boldly chooses to hide just about everything from the viewer, letting them linger in the after-effects of death and decay. The movie’s opening sees villagers with lanterns searching a forest at night for a missing girl named Alba. Meanwhile, Mother Nature continues its course – the howling wind, the thick fog, the dark tree branches piercing the night sky, the wailing of night owls creating an atmosphere not unlike that of an Angela Carter adaptation. [You will find similar scenes in both “The Magic Toyshop” and “The Company of Wolves.“] The difference is that, in an Angela Carter book, the protagonist is barely aware of the death omens and that she is avoiding them at all costs in order to preserve her sanity. In Thirty Souls, Alba is probably already dead when that scene occurs, and prior to her disappearance, there is not a single moment in which she is not acutely aware of the death surrounding her.

In this semi-fictional O Courel the dead might mingle with the living, unseen and unheard, but their presence is acknowledged – in the objects left behind and tiny crevices from which their world seeps into ours. Alba, a thirteen-year-old girl, insists that she can feel them as a result of a gift (or curse) passed down by her grandmother. She narrates her first experience with the dead leaving her paralyzed in the middle of the night. She believes the region, and the people living in it, are situated at the “core of death,” and that there is something binding the living to the dead, something that drives countless “exchanges” between them. When Alba says, “I look for a mirror to make sure I don’t see them” and the viewer sees an empty mirror reflecting nothing other than an open window and a snowy field, the movie manages to instill a lasting fear, akin to being told by medium “your loved one is right behind you.”

Some of them remain inside their homes. Some return in fear. They snoop. They spy. They watch. Out of time, they no longer have time. At least not like us.

Alba is not at all wrong in her observations. The people in the region are living in harsh conditions, and often chase away their grief by doing chores. They are, in various scenes, getting ready to boil a whole chicken, milking their cows, working the fields, or visiting and cleaning gravestones. Meanwhile, their children are receiving all the modern education that the community can afford: a scene features Alba, very much alive, going through a local version of the game “exquisite corpse” (a collaborative storytelling game made popular by the Surrealist movement in the 1920s) with her classmates and building a chain-story. The teacher even encourages the kids to preserve the element of mystery.

Mystery and reverence, but also Galicia’s past, one of slavery, fighting against oppressors and the more recent decades of bankruptcy and emigration, are major themes in Thirty Souls. There are folk tales like the moura encantada kidnapping a girl named Sabelina and frying her in a pan, (with the mandatory accompanying limerick) or the Celtic bard whispering the future of the community from behind the leaves. “Galicians had to protect their identity,” the schoolteacher recalls at one point – and a part of this identity was apparently being encouraged to keep their dead close by. For lovers of folk tales or fans of Clive Barker’s “Book of Blood,” this aspect will come as no surprise: one character in the 2020 “Books of Blood” adaptation states that in the beginning, people shared the same space as the dead and were happy to do so. It was only when industry invaded and culture developed that they moved their dead to cemeteries, and then even further out of the more populated city spaces. Portuguese author Jose Saramago even envisioned in his book “All the Names” a world in which there are so many dead, that they vastly outnumber the living and lead to more and more cemetery spaces (re)claiming urban areas.

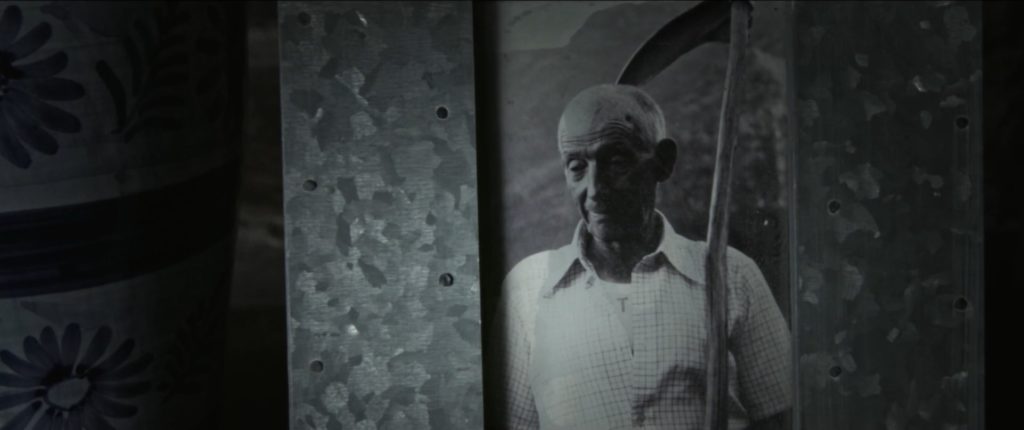

In the O Courel of Thirty Souls, the dead do reside in Villamor’s cemetery, pointing to an industrial community (a scene even features a factory where a worker is operating heavy machinery), but the local priest asks a rhetorical question about this particular arrangement: “how much of that is modernity, and how much is convenience?” He encourages people to maintain a connection to their lost ones, to honor them and to keep on loving them. Even though times have changed, the people remain wary of disrespecting the dead, and the dead linger in their thoughts. Locals often recount their own version of carving pumpkins for All Souls’ Day, their children even learn about Halloween in school, but a montage of the many photos of departed relatives in Alba’s grandmother’s house (one of the most powerful scenes of the movie) reflects that the dead are, in fact, still sharing the spaces of the living:

She remembers all of them, but I know that is because they are still here.

The culture around Alba is so death-infused that people have become very accustomed to death rituals and omens. Residents remain halfway between awareness and blissful ignorance towards the reality and randomness of actual death. They seem numb and removed and when tragic events happen, there is no strong emotional reaction as one might expect. A boy accidentally shoots himself with a rifle during a hunting trip. A wild animal is eaten alive by dogs. A group of kids watch a classic horror movie and don’t understand why it’s so special, can’t make out a single interesting thing about it. Meanwhile, Alba’s education level is making her more and more distanced from her community, because unlike her peers she is painfully “death-aware” as a result of her gift. When the movie lets the viewer see with her eyes, the dead appear in the form of “Will-O’-The-Wisps” (fairy lights) but because they are also visible during the day, it does cast a shroud of doubt on everything Alba is saying. Is she just an impressionable young girl who is obsessed with death, or is she really able to pierce the veil?

In any case, Alba is studying English and becoming aware of the existence of communities where the living don’t carry the smell of the dead. The realization that there are places where people can wear scary costumes and be rewarded with candy is making her growing unease even worse. In despair, she seeks out the homes of those who, willingly or not, left O Courel. It’s unclear whether she’s looking for a means of escape, or one of resistance. As Alba is sifting through documents and discovering dates with mounting horror, she sees those dates are becoming more and more recent. She is joined in her search for answers by Samuel (one of her classmates) and together they explore one last house, where they discover creepy-looking dolls and all the previous owners’ clothes left behind, the inhabitants of the house simply gone without a trace.

Similar to Stephen King’s “It,” the inhabitants of the region seem unaware, or at least unfazed by the larger goings-on, just like those in the town of Derry, Maine. Also, similar to M. Night Shyamalan’s “The Visit,” Alba and Samuel are scared that someone might find them. The kids retreat to the basement, and the scene grows in intensity until it reaches a Lynchian finale, managing to leave a huge (and very intended) hole in the narrative. Scenes like this are what might make the movie appeal to horror lovers, because they leave viewers reflecting on their own attitudes towards death. The first time Alba sees a “light,” the scene has an ineffable quality, with the slow camera movement circling rivers, forests, caves, and then resting on Alba’s visage. The second time, a slew of blue lights rises up from the remaining objects in a derelict house and form a sight akin to a fantasy setting. After Alba mentions the mirror method, the atmosphere becomes more oppressive, the fear is more pronounced. There is something especially terrifying about viewers not being able to entirely sense what Alba senses. One almost wishes that the dead would scribble their stories on some bathroom mirror, or a piece of paper, or even a character’s flesh – that would be a relief. But the departed are silent in Thirty Souls, and the movie uses natural light and heavy shadows to portray the ominous house interiors as being sum parts of the total limbo that shrouds the community.

Thirty Souls’s many techniques are better left for the viewer to uncover, as they are more important than the plot itself. The film relies on authenticity and immersion, featuring a cast of non-actors essentially playing fictional variants of themselves. Alba Arias’s performance is stunning – transcending the “amateur performance” label, with numerous close-ups highlighting her unrest when coming into contact with the dead. In stark contrast, the audience gets to see Alba in the classroom among her peers, where she is mostly happy, relaxed, while still being aware of the harsh reality outside the walls of knowledge. While it’s never clear to the viewer whether she really sees dead people or is just resisting a deeply spiritual culture that has left her scarred, the audience sees a girl the same age as Alba who doesn’t mirror her in any way – just a normal teenager hopeful about the future. (There is, however, a great scene in which a dog senses the presence of a “light”, which might tip the balance scales for many viewers). Lastly, there are two very young actors playing characters with a burgeoning awareness of their surroundings, pulled back from their reveries by doting parents.

Why does Alba disappear and where does she go? The answer requires one to piece together the challenging puzzle that this movie offers. Did the others disappear in the same way? Why was the house unlocked? Alba herself says at one point “if you look closely, you can see them” – and so the viewer is forced to watch the movie looking for any hint or clue. The rewards (like seeing the lights for the first time) are a lot more satisfying than the occasional frustration caused by the film veering in experimental territory.

Whatever the resolution to the very tantalizing mystery might be, one thing is clear: Thirty Souls is a miraculous film, both informative and evocative, and because of the magical realist approach, Toucedo makes O Courel seem like a veritable Macondo. The lyrical, observational approach will be a deterrent for many viewers looking for pure plot and thrills, and even fans of slow-burn horror will have problems with the first half unfolding at a snail’s pace, especially if they haven’t seen a nature documentary or two. But in depicting all these details, all that living, Toucedo doesn’t just break the flow when needed – she delivers not one, not two, but three of the scariest scenes of 2018, managing to convey a portrait of life enduring while being strangled, overwhelmed by the odor of death from all directions.

Thirty Souls is available to watch on Kinoscope and to rent on Mujeres De Cine VOD.

More Film Reviews

Unspeakable: Beyond the Wall of Sleep is a 2024 horror film, written and Directed by Chad Ferrin. The film is an adaptation of H.P. Lovecraft’s short story Beyond The Wall… I love good old-fashioned mockumentaries, especially when they’re done right. Lake Mungo, Ghostwatch, Hell House LLC. and Savageland are just some of my personal favorite mockumentaries—these films manage to create… In a previous article of mine, I mentioned the creation of found footage and incorrectly attributed this title to Eduardo Sánchez and Daniel Myrick’s The Blair Witch Project (1999). Although… Evilenko is a 2004 English-language Italian true crime horror/drama written and directed by David Grieco in his first feature-length film. Malcolm McDowell plays the Soviet Union’s most notorious serial killer,… South Korean cinema has carved out an incredible niche releasing thrillers tinged with a deliciously dark tone. From brutal revenge-fueled classics like Old Boy to soul-destroying crime thrillers often focused… It was about halfway through watching Rob Jabbaz’s debut feature The Sadness that I realized I was in the hands of a maniac. Taipei resident Kat (Regina Lei) is hiding…Unspeakable: Beyond the Wall of Sleep (2024) Film Review – An Inventive Yet Deferential Reimagining

Hunting Matthew Nichols (2024) Film Review – A “Blair Witch”-Inspired Slow Burn Mockumentary

The McPherson Tape (1989) Film Review – Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner

Evilenko (2004) Film Review – A Crime Horror Flick Ripped From The Headlines

Midnight (2021) Film Review – A Master Class in Building Tension

The Sadness (2021) Film Review- A Powerful, Repellent Horror Spectacle