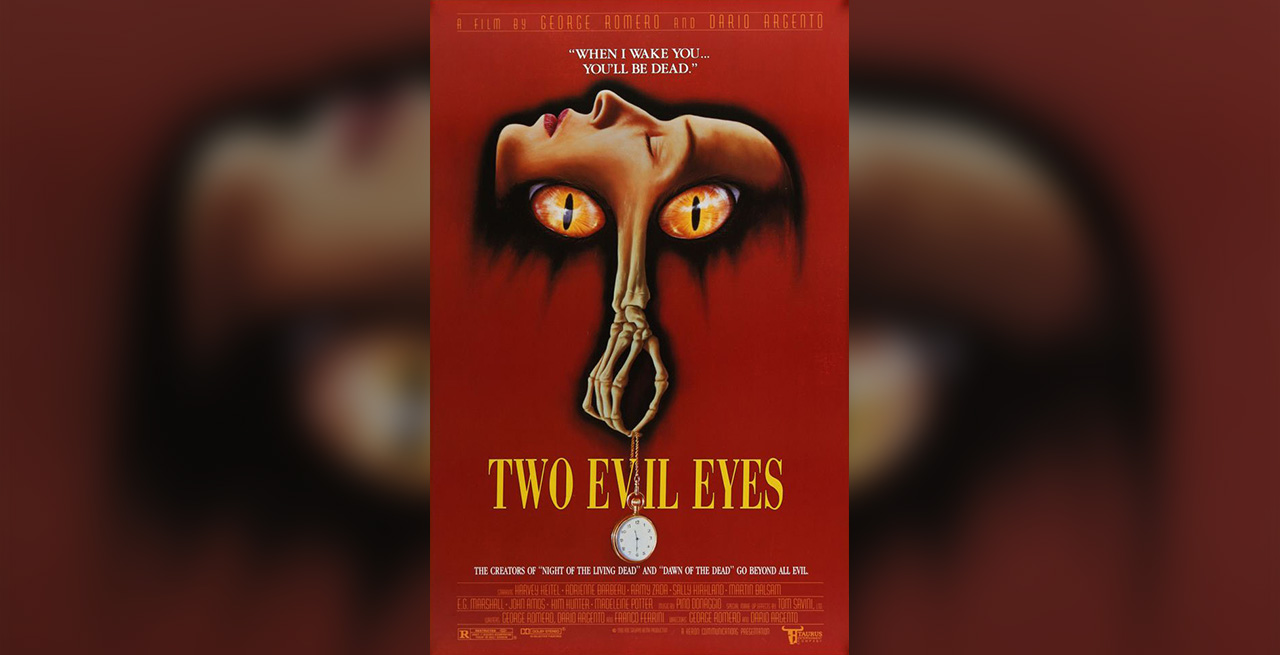

Horror filmmaking royalty collides in Two Evil Eyes (1990): a star-studded yet relatively niche anthology horror from the depraved minds of Dario Argento and George A. Romero. The dastardly duo first collaborated together on the eternal classic Zombi in 1978, more commonly known as Dawn of the Dead, where Argento re-cut, re-scored (a groovy Goblin record was thrown into the mix) and re-released Romero’s living-dead smash-hit for a bloodthirsty European market. Twelve years later, they fused their singular styles into a two-part anthology, operating as a delectably eerie melange of gothic storytelling.

Two Evil Eyes adapts two Edgar Allan Poe stories: Romero opts for the hypnosis-zombie chiller “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar” and Argento helms the highly-imitated classic “The Black Cat”. The translations to screen are a hodgepodge of ideas, techniques, and genre icons that act as a flawed but intriguing exercise, and a film that renders the slightly treacherous search for a copy (in the UK, anyway) very worthwhile for fans of cult cinema and horror auteur completists.

The lore is as alluring as the picture itself. Writer Stephen King (The Shining, Carrie) and director John Carpenter (Halloween, The Thing) were last-minute dropouts, leaving just Argento and Romero to pick up the pieces and build an ode to the ‘Godfather of Gothic Horror’. Alas, history has failed Two Evil Eyes, it now subsides in the weird, forgotten annals of illustrious filmographies. If you are not intrigued by its elusive legacy, then prepare to be intrigued by its nightmarish contents.

Romero’s segment rolls first; Jessica Valdemar (scream queen and John Carpenter favourite Adrienne Barbeau: The Fog, Escape from New York) is cheating her terminally ill husband Ernest out of his fortune. Her lover, Dr. Robert Hoffmann, hypnotises Ernest on his deathbed and makes him sign off his millions to Jessica. Bulletproof plan, right? Never underestimate the power of the subconscious. Disaster strikes when Ernest dies whilst under hypnosis. He is spiritually locked in between death and life… and physically locked in a fridge freezer, because Jessica and Robert decide that preserving his body until the money comes through would of course be the most logical and hygienic decision.

Melodramatic exposition and iffy dialogue soundtracked to an overbearing score take up large portions of this segment. Romero takes Poe very literally and loyally; he ditches exciting visual flourishes in order to ‘play it down the middle’. The grand finale is worth sticking around for, however. Blood splatters across dollar bills and chandeliers; Romero condenses Poe’s matricide-gone-wrong short story to a few shots that frame greed as the real evil. Fans of horror regular Tom Atkins rejoice; the beloved Halloween III: Season of the Witch and Maniac Cop star appears for a terrific stint as a detective towards the end of the segment. Also, the practical effects for Ernest’s frozen (and subsequently defrosted) state are brilliantly executed by none other than Romero’s right-hand man, legendary special effects supervisor Tom Savini, someone who makes a hilarious acting cameo as a tooth-plucking serial killer later on in “The Black Cat”.

Speaking of, Argento’s segment is vastly different in terms of adaptation, style, and personnel. If Romero’s take on Poe could be described as ultra-faithful, rigorous, and slow-burning then the words singular, unrestrained, and unhinged would be fair descriptors of Argento’s stab at the material.

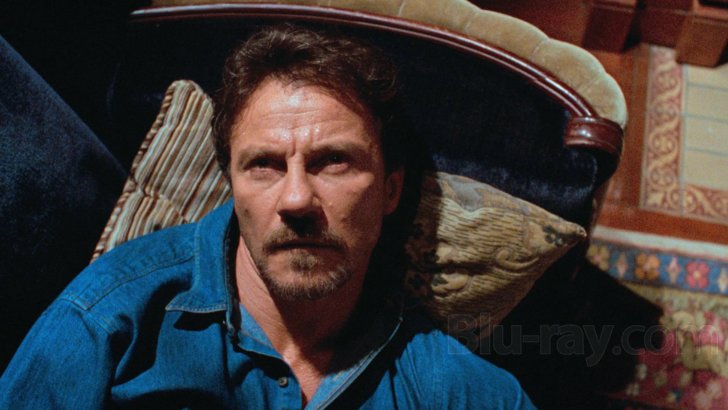

Rod Usher (played by THE Harvey Keitel) is volatile, abusive, and an alcoholic. He is also a crime scene photographer, which is a plotline entirely fabricated by Argento. Why? Well, when Rod attends a homicide in the first five minutes, we see a bloody, outstretched body sliced in half as a result of a huge, shiny pendulum that swings back and forth. Even though the body is long deceased, Keitel activates the machine and gets his kicks watching this violent spectacle in action, just like the audience does. A violent, voyeuristic set-piece that is characteristic of Argento’s style, but it is not completely without purpose. It is a reference to another Poe story: The Pit and The Pendulum, and a shining example of Argento’s ability to forge nuanced grotesquerie.

Following that excursion, Rod takes a dislike to his girlfriend’s beloved black cat, only for it to haunt and taunt him for weeks as he spirals into a discombobulated, drunken breakdown. There are perspective shots from the POV of a cat that is brilliantly photographed, and there are memorably creepy dark-room scenes where Rod is developing his crime-scene snaps. Keitel plays a hateful abuser to frightening perfection, a performance very similar to another role he had in the early 90s- Abel Ferrara’s gritty classic Bad Lieutenant. Luigi Cozzi, the Italian genre filmmaker, friend of Argento, and the 2nd AD on Two Evil Eyes, claimed that Keitel had a ‘passionate temperament’ and staged a tantrum about the costuming, a tension undoubtedly contributing to the manic, unpredictable aura attached to the character of Rod. This segment has everything, from dream sequences depicting medieval torture to revolting corpses of humans, cats, and half-human/half-cats that rot in the walls of a haunted Pittsburgh house.

Whilst some may pinpoint this film as the beginning of Argento’s decline into a filmography that was panned critically and forgotten historically (Romero too, although to a lesser extent), Two Evil Eyes is an exercise worth celebrating for what it is, rather than who and what could have been. A creative relationship between two horror legends immortalised onto celluloid: the unification of distinct cinematic approaches that adapt the formidable literature of Edgar Allan Poe. A film that is beneath Romero and Argento’s output of original material, but nevertheless deserves plaudits for its lofty ambition, humble dedication, and enthralling derangement!

More Film Reviews

When it comes to lost media, there are a variety of reasons as to how the media came to be missing in the first place. But, by far the most… Billed as “A collection of Canadian shorts premieres, covering a bit of unusual, the surreal, and the lighter side of horror!”, the Thursday night line up at Blood in the… Nowadays manga adaptations are commonplace, and often fairly inevitable – however, this wasn’t always the case. Prior to the 1970s, adaptations of manga were a rare sight, especially live-action ones…. In recent years, foreign films have taken the horror genre by storm with such titles as Parasite (2019), Raw (2016), and Veronica (2017). The Argentinian director Demián Rugna‘s 2023 film,… In 2017, the United States Air Force carried out an airstrike in the Nangarhar Province, Afghanistan. Deploying the largest non-nuclear bomb in their arsenal (the MOAB), they aimed to destroy… There have been many horror films that tackle the theme of trauma in recent years, but this one really pushes things a bit further. Traumatika is a 2024 horror film…Effects (1979) Film Review – The Snuff Of Legends

Funny Frights & Unusual Sights Short Film Reviews – Blood in the Snow Film Festival 2024

Dump, Hip, Bump: Give it to Me Guys! (1969) Film Review – Smashing the Patriarchy One Judo Chop at a Time

When Evil Lurks (2023) Film Review – A New Take on Possession

The Lair (2022) Film Review | Toronto After Dark Film Festival

Traumatika (2024) Film Review – Trauma is a Disease [Frightfest]

![Traumatika (2024) Film Review – Trauma is a Disease [Frightfest]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Screenshot-2024-07-29-5.24.09-AM-365x180.png)