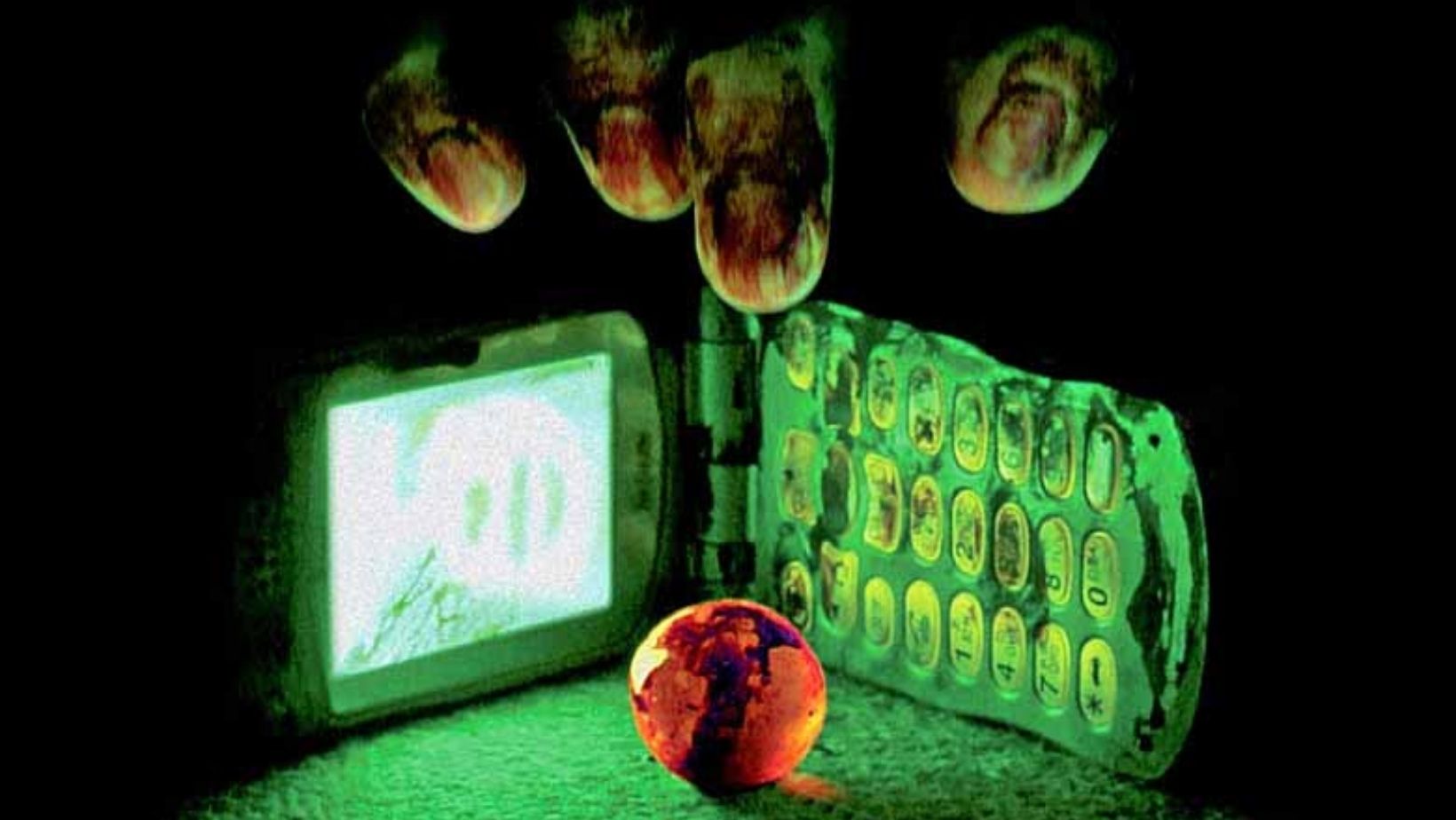

It’s well hypothesised that the late 90s-early ’00s ‘J Horror’ boom was inspired thematically in parts by the country’s post-war advancements in technology and economic prowess that had gradually begun to stagnate by the 90s. A zeitgeist of fiscal depression and disappointment opened the door in which crept the eponymous genre, wrapping a slimy, cold hand around the culturally specific anxieties of Japanese horror audiences and refusing to let go. Famously, Hideo Nakata’s Ringu explored the viral spread of a VHS-borne curse, whereas later in 2005, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s unimaginably bleak Kairo prophesied an apocalypse of social withdrawal thanks in no small part to the worldwide surge in Internet usage. Nestled between these two powerhouse pictures was legendary director Takashi Miike’s take on the cell phone, still in its humble beginnings, as a vessel of malevolence. From a director who seems to swing so frequently and violently between trash and treasure, 2003’s Chakushin Ari sits somewhere in the ‘just fine’ category: it’s no Audition, sure, but it’s also no Zebraman 2: Attack on Zebra City.

Known in English as One Missed Call, the film follows Yumi (Ko Shibasaki), a young woman who finds herself enmeshed in a mysterious series of deaths seemingly triggered by a voicemail from the future, and the world’s catchiest ringtone. With the help of Detective Yamashita (Shinichi Tsutsumi) – also seeking answers for his sister’s death – Yumi must solve the curse and appease the spirit behind it before her own phone starts ringing.

Perhaps it’s unfair to compare Chakushin Ari to the main big hitters of the J-Horror boom, but it’s hard not to when the film seems so desperately to want to belong in the pantheon of such iconic films as Dark Water and Ju-On. The film is often (again, perhaps unfairly) decried as part of the subgenre’s eventual death knell with a lukewarm reception upon release and a reputation marred by one of the lowest-rated American remakes of all time. Although only five years had passed since Hideo Nakata’s ground-breaking tech-terror had crept through screens into the nightmares of viewers, five years of rip-offs, sequels, and reboots is a very long time for audiences oversaturated with the image of the crawling, croaking onryo.

From 2022, the idea of a ‘cursed voicemail’ might feel out of touch as it’s a medium seemingly forgone in favour of instant or text messaging, but the call itself is where Chakushin Ari holds its chills even today – especially with a generation so avoidant of picking up the receiver. How many of us have stared at our ringing phone, waiting for the number on the screen to disappear so that we can continue to doomscroll in peace? There’s also horror to be found in the large scale circulation of communication and the modern-day memetic nature of informational spread. It’s no longer a case of ‘if’ your phone will receive whatever’s going around, but ‘when’.

Unlike the existentially dreadful and subtle simplicity of Ringu’s seven-day death sentence, Chakushin Ari tries to go all out on big scares. Priests are propelled like rag dolls in a live, over-the-top TV exorcism. Limbs are shattered and sliced by a speeding train. Rotten, green skin slops off the bones of a walking corpse. This is where the flashes of Miike genius shine through in twisting, bone-cracking gore. But they don’t quite flash bright enough to light up long swathes of dull investigation, in which Yumi and Detective Yamashita try to piece together a puzzle made of weak parts. The teddy bear, the red candy, and the inhaler all feel like desperate attempts to capitalize on creating an iconic, recognizable ‘symbol’ for the film, à la Sadako’s television or Kayako’s throaty death rattle.

At its strongest, Chakushin Ari leans into Miike’s talented touch, with colour and camera work often reminiscent of the sepia, sickly hue that runs through Audition’s nastiest moments. And, much like Audition, there’s a poignant theme of trauma begetting trauma beating through the film’s undertones. As Yumi follows the supernatural calls down a rabbit hole of a fraught parent-child relationship, the abuse enacted by her own mother comes back to haunt her. It’s here where, after all the scares both tacky and terrifying, Chakushin Ari presents a surprisingly heart-wrenching look at how pain leaves a stain that seeps through peace, shattering the silence like a ringing phone.

More Film Reviews

An ancestry test taken on a whim reveals a sprawling British family Evie never expected. Offered an all-expenses paid trip to England as part of a wedding invitation, this whole… Down and out, and possibly facing a midlife crisis, Georges decides he wants to change things up. The first thing on the agenda comes from a unique purchase, a deerskin… Despite being one of Japan’s biggest film studios throughout the late 40s and 50s during the golden age of Japanese cinema, Daiei was struggling by the mid-60s and had… Selected to cap off the closing night of Fright Fest 2021, The Advent Calendar has come to the attention of horror fans as one of the titles already announced as… I love good old-fashioned mockumentaries, especially when they’re done right. Lake Mungo, Ghostwatch, Hell House LLC. and Savageland are just some of my personal favorite mockumentaries—these films manage to create… Kingdom of the Apes is a 2022 Japanese thriller, written and directed by Shūgō Fujii. Making his directorial debut with Living Hell (2000), Fujii gained notoriety with his recent mystery thriller…The Invitation (2022) – Downton Abbey with More Accurate Aristocrats

Deerskin (2019) Movie Review by Quentin Dupieux – “Killer Style Never Looked so Good”

Secrets of a Woman’s Temple (1969) Film Review – Temptation, Torture, and Treachery

The Advent Calendar Film Review – Eat Chocolate or Die!

Hunting Matthew Nichols (2024) Film Review – A “Blair Witch”-Inspired Slow Burn Mockumentary

Kingdom of the Apes (2022) Film review – A Fable of Japanese Society

Writer, podcaster and reviewer over at HornBloodFire.

Lover of gore, ghosts and girls getting their own back.