The genre, now referred to as “Pinky Violence”, would absolutely dominate cinema in the early 70’s, which was largely helmed by Toei in their focused attempt to pump out many popular films to quickly and cheaply as possible to meet their quota of two new films every fortnight in order to obtain exclusivity contracts with cinemas. Pinky violence is an amalgamation of genres favoured by Toei during this movement, although the main pillar, which is synonymous with the term, would be their “Sukeban” films. Supposedly created by Toei director Norifumi Suzuki, the slang word “Sukeban” (Girl Boss) would become the major cash cow of Japan’s equivalent to grindhouse cinema, roughly mirroring America’s blaxploitation movement. Sukeban films would combine sex and violence with the largely independent youth cinema of the late 60’s. The women in these films were the antithesis of conservative Japan up until that point: unladylike delinquents challenging gender norms who were totally uninterested with the concept of marriage or motherhood, generally being unemployed and vagrant but also strong along with independent.

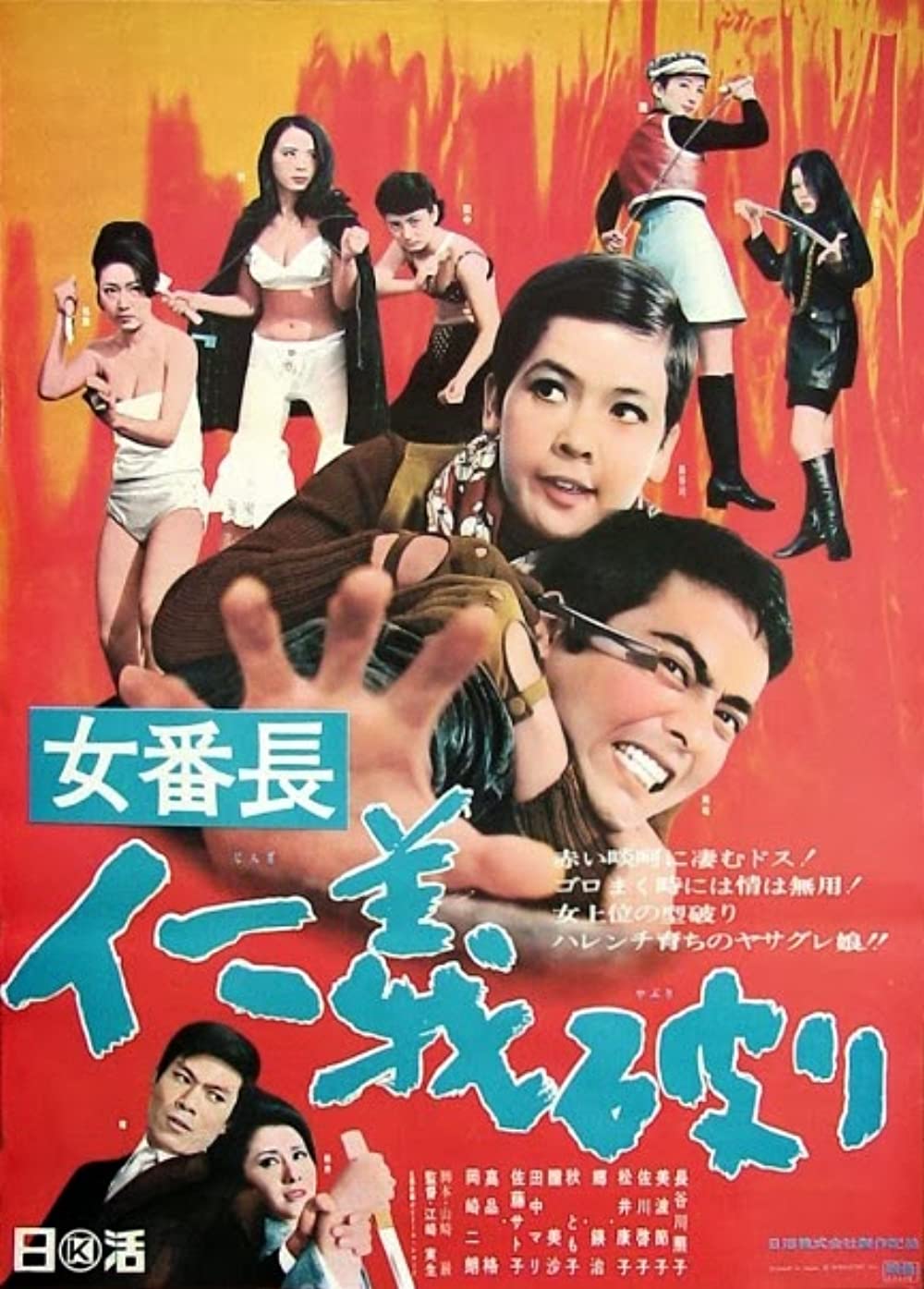

The fire that was sukeban cinema ignited suddenly and was a flame that burnt incredibly hot but also incredibly fast. The genre truly started building momentum in 1971 but was largely dead by the end of 1974. The origins of sukeban are a little harder to determine in such a busy genre with three studios – Nikkatsu, Toei and Daiei – all attempting to one-up each other during the birth of the genre. Nikkatsu were the first to release a sukeban film called “Girl Boss: Broken Justice” in February 1969, but the subject itself predated this film. Perhaps the earliest depiction of sukebans in popular media would come from the manga world, and one author in particular – Taro Bonten.

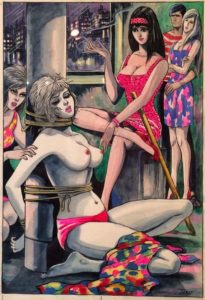

After a heavy does of disillusionment following Japan’s defeat in WW2, Taro Bonten would enlist in art university and soon after start making money painting kamishibai boards. By the 50’s, kamishibai would fall out of fashion and he would turn his artistic attention to manga, providing artwork for the many popular shoujo magazines of the day. By the end of the decade, he would focus more on tattooing, subsequently becoming an accomplished tattoo artist regarded by many later on as one of the most influential tattoo artists in 20th century Japan. In the 60’s, however, he would start working on manga again, this time shonen action. By 1967, he was able to create his own gekiga stories and this was when he started developing various sukeban works- perhaps the first artist to tackle this genre. The first in his series of standalone titles under the collected name “Modern Delinquent Girl Stories” was “Okyo the Stranger” would published by “Manga OK” magazine in October 1967, followed by “The Tattooed Okei” and “Female Dog In Yokohama” later that same year.

Filled with sex and violence, the content of these works was hardly ground-breaking but the focus would be. Each one of these stories is told from the perspective of a sympathetic yet delinquent protagonist. Time is taken to explore the emotions of these characters instead of observing events from the outside.

Taro Bonten would find further success the following year with his first long running manga “Inoshika Ocho” being serialised in “Manga OK”. This would later be adapted by Toei in 1973 under the title of “Sex and Fury” and would become a cult classic outside of Japan. Whilst not concerning sukebans, Ocho Inoshika still follows a strong female character navigating modern Japan’s urban underbelly on a trail of revenge. In September 1969, Bonten would revisit his earlier sukeban manga and publish his most successful and longest work “Konketsuji Rika“. Expanding on themes first explored in “Okyo the Stranger” and “Female Dog in Yokohama“, “Konketsuji Rika” would follow the life of a young mixed race woman Rika (konketsuji was a racial slur against mixed-race people with “mud blood” being the closest English equivalent) as she gradually becomes a sukeban.

“Konketsuji Rika” takes quite a unique approach to storytelling. Whilst most manga at the time would focus on episodic chapters which could be read largely standalone (favourable for printing in weekly/monthly manga magazines), “Konketsuji Rika” would be written almost like a visual novel with a continuous story unfolding. The manga unexpectedly does not start with the titular Rika, but instead spends the first four chapters focused on her mother; in particular her r*pe at the hands of American soldiers stationed in Japan during the Korean war and the subsequent birth of her mixed-race daughter.

The next few chapters then focus on Rika’s childhood; largely the racist bullying encountered from other children as well as the shame and anger at finding out her mother was working as a prostitute to pay for her schooling. Every event at the start of the manga actively shapes Rika’s personality, each chapter adding an extra facet of anger and angst to the girl who would always be regarded as an outsider. The final push comes when she is a teenager and is sexually assaulted a number of times- the worst of which at the hands of her mother’s boyfriend. From this point she knows that she is the only one who can protect herself. Soon after two men try to assault her when she’s walking at night, though Rika takes matters into her own hands and beats them both with a metal pole. Unbeknownst to her, these men are gangsters and soon she is targeted by a local gang boss intent of making her pay for her actions. This path eventually leads to her arrest and sentencing to a reform school (basically a juvenile detention centre). This is where the true story begins and where the final character of Rika is realised. At the school she encounters fellow delinquents as well as another mixed-race girl and eventually forms a gang.

Instead of being published in a usual manga magazine, “Konketsuji Rika” was published in the pop culture magazine “Weekly Myojo”. The manga would prove massively popular and would be published until 1973, amassing a total of 214 chapters. It is clear the manga would have a large influence on sukeban cinema with almost every Toei film relying on the reform school trope, as well as many other facets of the sukeban character started by the manga.

After middling success with their first sukeban film “Girl Boss: Broken Justice”, Nikkatsu would go on to make another film “Cruelty of Women’s Lynch Law”. This follow-up proved extremely popular, as did their lead actress Meiko Kaji (then still going by the name Masako Ota) and a year later the massive “Girl Boss: Stray Cat Rock” would be realised as a result. Alongside Nikkatsu, the struggling Daiei (who were partnered with Nikkatsu at the time) would release their own line of sukeban-inspired films called “Highschool Student Boss”. Toei finding themselves outside of this newly emerging genre found it necessary to compete and produced their own film named “Three Pretty Devils“. This would lack the unique style and substance of Toei’s later films in the genre and seems to have been rushed out to fill a gap in the market, largely copying Nikkatsu’s offerings- or perhaps test the waters before committing too much time and money to an unexplored emerging genre.

Later that year, Toei would make a more convincing impact on the genre with “Delinquent Girl Boss: Blossoming Night Dreams “. The charismatic Reiko Oshida (winner of the 1966 International Teen Princess pageant) would be cast as the lead named Rika, which seems too much of a coincidence, with Keiko Fuji providing the theme song “Blossoming Night Dreams” which the film took its title from. Presumably Toei were influenced by Nikkatsu’s “Stray Cat Rock” with their casting of singer Akiko Wada and use of her music throughout to create not just a film but a multi-media celebration of à-la-mode pop culture.

“Delinquent Girl Boss” starts out in a reform school where we are introduced to Reiko Oshida’s character as well as the girls who would later form her gang. This starting feels straight out of the “Konketsuji Rika” manga, and for the rest of the film Reiko is very much the protagonist who we follow throughout, not too dissimilar to Rika. This focus on a singular protagonist really set Toei apart from Nikkatsu and probably made it easier to market. Nikkatsu’s films (as well as “Three Pretty Devils“) made the entire gang the protagonist with no member truly standing out from the ensemble. With “Delinquent Girl Boss“, there is no doubt that Reiko is the main character and the glamourous Reiko Oshida would feature front and centre on the posters for the three remaining films of the franchise.

For all the similarities between “Delinquent Girl Boss” and “Konketsuji Rika“, there would be one missing ingredient: fury. Whilst “Konketsuji Rika” is a seethingly violent manga, “Delinquent Girl Boss” focuses on making their main character far more genial than Rika, possibly to appeal to a wider and more casual audience, though she still retains Rika’s youthful naivety and tough rebellious spirit. Whilst there is plenty of violence and tragedy, the overall feeling is much more upbeat.

Norifumi Suzuki would be the one to introduce that anger and fury into the genre. After the fourth “Delinquent Girl Boss” film, Reiko Oshida would quit acting in order to focus on her career as a singer, thus there was now an opening for a new star. Rather than continue to keep rehashing the same films, a new series was started- “Girl Boss Blues” featuring the legendary Reiko Ike as the lead. The following six “Girl Boss” films would all follow the same reform school formula and Toei even created another closely-related series of four films titled “Terrifying Girls’ Highschool” which would take place entirely in reform school with more focus on the pinku aspects.

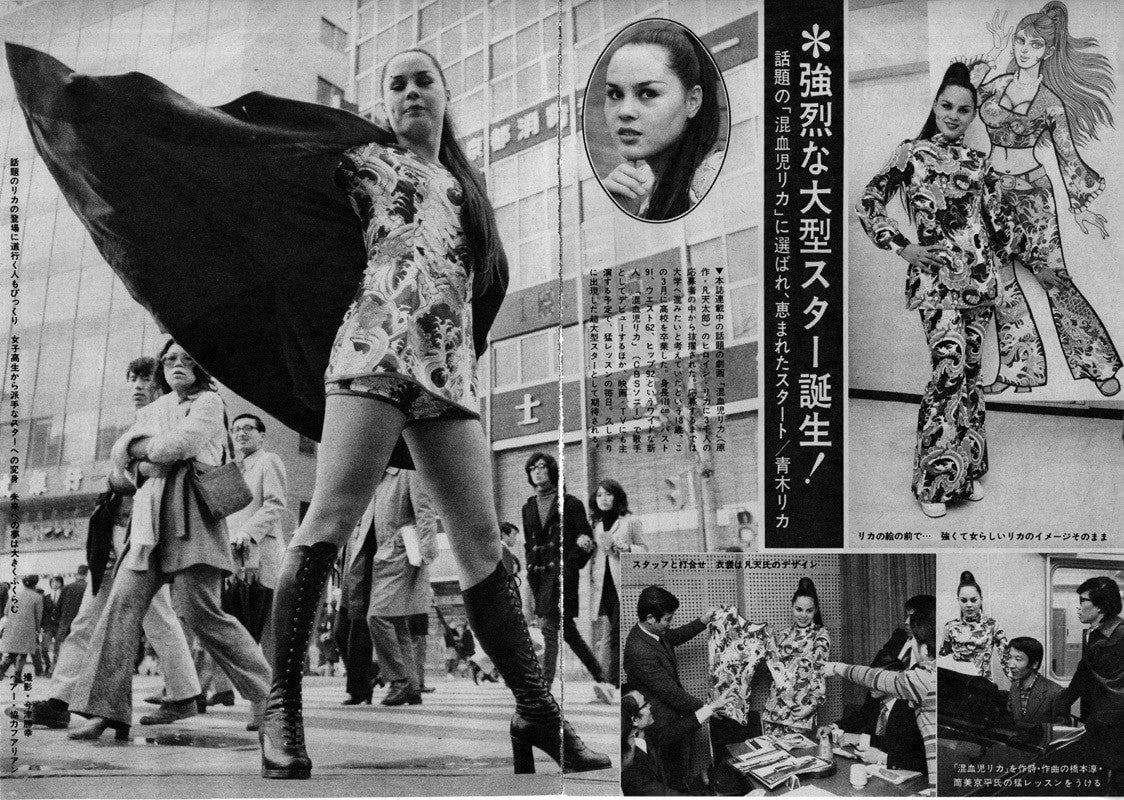

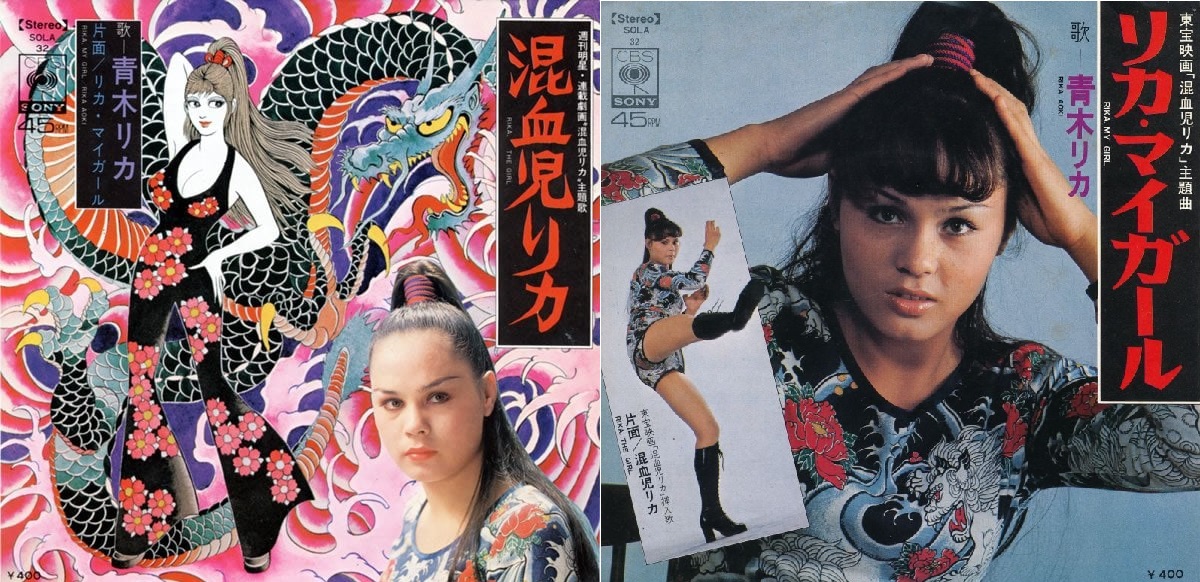

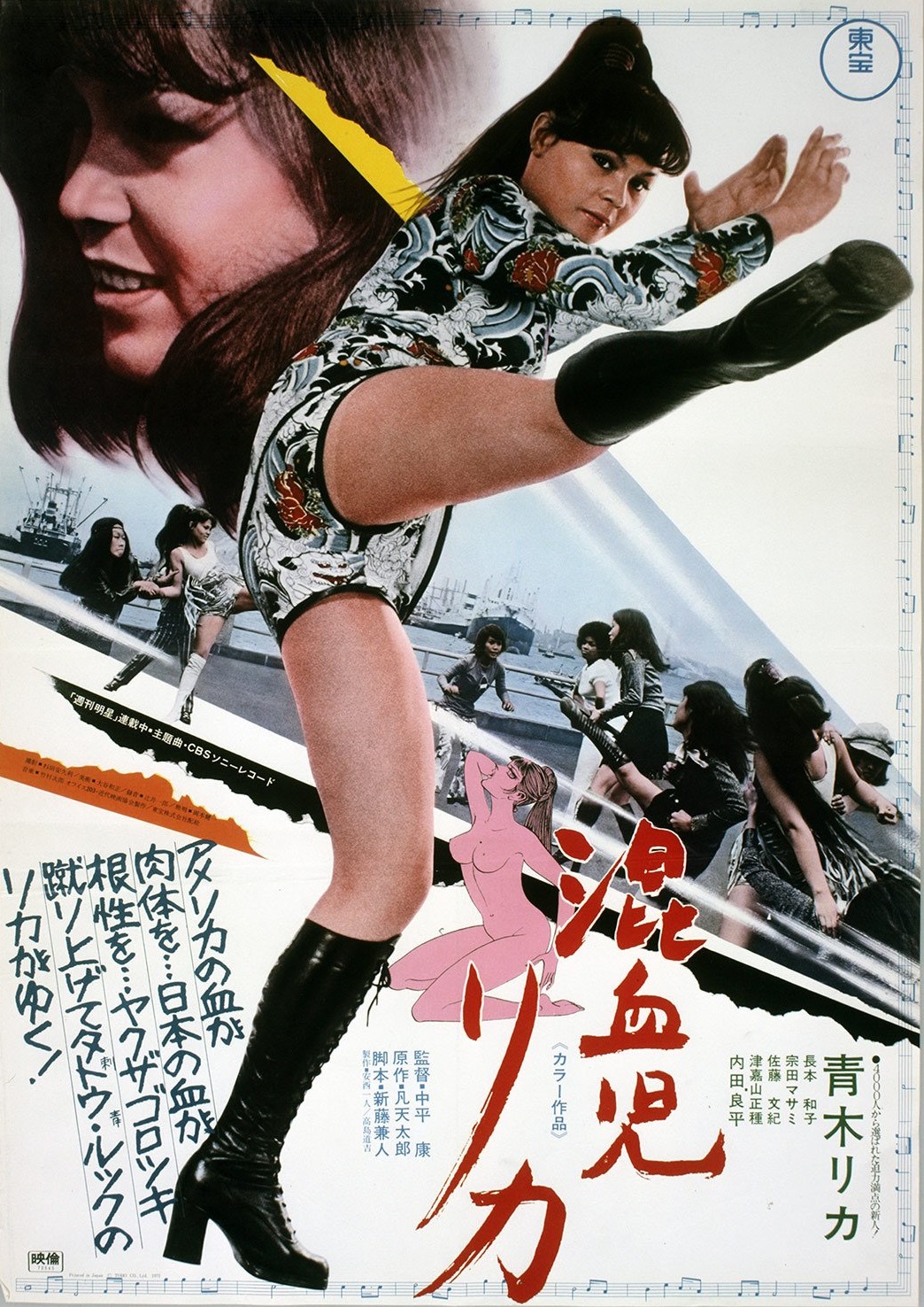

By 1972, Toei had made two “Girl Boss Blues” films helmed by Norifumi Suzuki and it was decided that “Konketsuji Rika” would get a film adaptation produced by Kindai Eiga. Presumably there wasn’t a large selection of mixed-race actresses to fill the role of Rika, so “Weekly Myojo” ran an extensive casting competition for the lead. The victor in February 1972 would be Rika Aoki. Being Caucasian/Japanese mixed-race as well as an impressive 170cm tall, Rika Aoki would be a perfect choice to match the stature and looks of her manga counterpart. The casting was a big deal and almost immediately a soundtrack was recorded with Aoki herself singing. This would consist of 2 tracks- “Konketsuji Rika” (listed as the manga theme) as the A-side and “Rika, My Girl” (the film theme) as the B-side. It is clear that this was made to appeal to fans of the manga with Taro Bonten’s illustration taking precedent over Rika Aoki. Being able to rely on the manga artwork to sell the record shows how popular it had become by then.

Two months later to coincide with the upcoming film, the record was re-released this time with the tracks inverted so the film theme was the A-side and the sleeve art using photos from the film’s promotional shoot. “Konketsuji Rika” would finally be released in November 1972 by Toho to reasonable success. Whilst the film is a faithful adaptation of the manga, too little care is taken on fitting the story to the film medium. The film practically uses the manga as a storyboard which results in bizarre pacing. Whilst sudden location changes between chapters of the manga isn’t particularly noticeable; the film appears disjointed and frenetic, almost like transitionary scenes have been cut entirely. Unless the viewer was intimately familiar with the source material, they would have probably been confused for the first 20 minutes.

On top of the pacing issue, there was also Rika Aoki’s acting. It is clear that she is an amateur and whilst her naïve rabbit-in-the-headlights vibe matches the character of Rika quite well, she simply lacks the screen presence to be able to sell the aggression and intimidation needed of the role. It perhaps weighed against the film that Toei had released “Girl Boss: Guerilla” and “Terrifying Girls’ Highschool: Girls’ Violent Classroom” in the three months prior to its release. Both of these films would feature the bombastic talents of both of Toei’s premiere pinky violence stars Reiko Ike and Miki Sugimoto in the lead roles, so “Konketsuji Rika” following them would feel somewhat tame and unpolished. Looking back retrospectively at “Konketsuji Rika” without knowing the history, it does seem like it is a lower-tier derivative of the Toei films. It has to be said that Toei’s own sukeban series did a far better job of adapting the themes and tropes of the Rika manga than the official adaptation ever would.

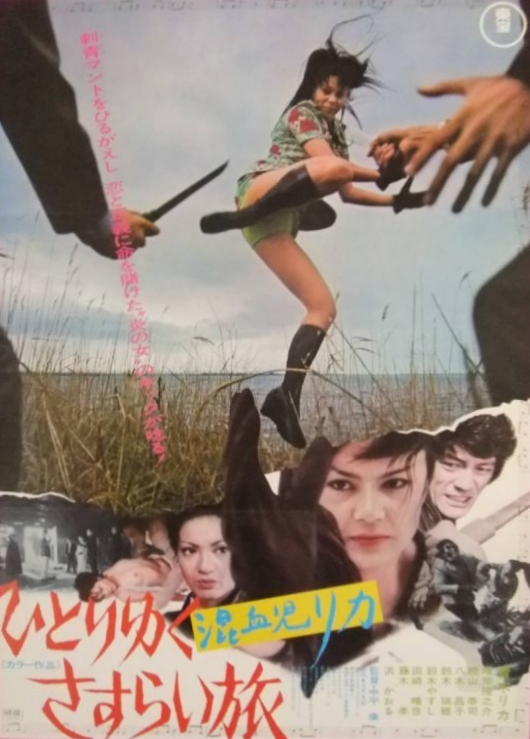

Four months later, the sequel “Lonely Wanderer” would be released, again beaten to the screen by Toei’s “Girl Boss: Revenge” and “Terrifying Girls’ Highschool: Lynch Law Classroom“, as well as their own Taro Bonten adaptation with “Sex and Fury“. Whilst the sequel is a large improvement on the first film with a clearer story and better performance by Aoki, it still feels like a pale comparison to the output by Toei who had now perfected their sukeban formula and were able to pump out new sukeban films on an almost monthly basis until the end of 1973.

Perhaps the nail in the coffin for Konketsuji Rika would be the third and final film “Juvenile’s Lullaby” released in June 1973. For this film Kozaburo Yoshimura would take over the director’s helm from Ko Nakahira. Whilst Nakahira had earnt his chops making HK action films and crime films for Nikkatsu in the 60’s, Yoshimura instead had worked mainly on dramas during the ’50s; a 62-year-old director certainly seems an odd choice for a genre so intent on capturing the zeitgeist of 70’s youth culture.

“Juvenile’s Lullaby” feels almost like a spoof of the series- not too dissimilar to the original “Casino Royale”. The film is full of bizarre sequences such as Rika beating off assailants with a baguette as well as a Benny Hill style chase through hanging laundry. In contrast to this, the main story is still as bleak as ever which makes the comedy even more out of place. One scene surrounding a kidnapped child about to be r*ped in order to make porn to be sold overseas has a joke about her rapist struggling to get erect which is ridiculously tasteless even by 1970’s standards. Comedy was by no means absent in the sukeban genre; Norifumi Suzuki would often integrate it into his films with decent success, though a certain amount of tact is needed to prevent it turning into farce. Whilst Suzuki had plenty of practice on this with his pre-pinky violence, tongue in cheek “Delinquent Boss” biker films and had perfected the art, Yoshimura seems unsure of the tone needed. Perhaps it is no surprise that this would be the penultimate film Yoshimura would ever work on.

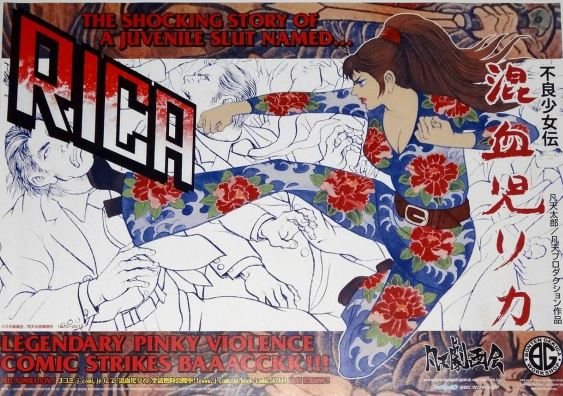

Rika Aoki would go on to star in a small role as a sukeban in Toei’s “Student Yakuza“ in 1974 before retiring from the film and music industry altogether. Whilst the manga would have two collected volumes published to coincide with the films, after the final chapter in November 1973 it would fall into obscurity. The contents were often said to be too extreme to ever be re-released, and Toru Shinohara’s (“Female Prisoner Scorpion“, “Zero Woman“, “Super Gun Lady“) signature mix of action, sex and violence would become the prominent form of pinky violence style manga for the next 2 decades and become perfect fodder for the 80’s straight-to-video V-Cinema format. The films would also share a similar fate with no home video release in Japan as well as being too extreme to be shown on TV; to this day, the only way to obtain a physical copy in Japan is to import the American DVD set.

Nowadays, the sukeban genre is remembered via the barnstorming classics made by Toei, though it would be fair to say all of those films owe their popularity and content to the ground-breaking manga written by Taro Bonten back in 1967. Fortunately, “Konketsuji Rika” is now available to read in its entirety for free online, as well as a print-on-demand service for physical volumes courtesy of Amazon.

More Reviews

The Moor (2023) Film Review – Cronin’s Atmospheric Horror is a Must Watch

In today’s world of flashy graphics and CGI, audiences have become immune to fantastical horror, pushing some writers to create content to test our boundaries with the extreme. In The…

Gorenography (2021) Film Review – A Conscientious Exploration of Extreme Cinema Directors

Gorenography is a 2021 documentary hosted by director Tony Newton. The documentary delves deep into the world of extreme cinema, divulging an uncensored, unbridled look at this niche underbelly of…

Ride Baby Ride (2023) Film Review

Ride Baby Ride is a tightly condensed short film that packs a powerful punch to the patriarchy in its 6 minutes. Director Sofie Somoroff is no stranger to conjuring up…

Bad Bones (2022) Review – Low-Budget Horror with Major Creep Factor

There are a few sins of horror movies making worse than the lack of originality. Every year theaters and streaming services are flooded with tepid horror movies churned out for…

Legend Of The Mountain (1979) Film Review – Triumphant execution of a typical Folktale-ish Narrative

Shih Chun is Ho Yun-Qing, an intelligent student who fails his imperial examination and, after failing to find a respectable job well, decides to become a manuscript copyist. His minimal…

Dead Northern Film Festival (2024) Short Films Day 1 – Scares Aplenty

Returning for its 6th year, the Dead Northern Film Festival is back to deliver another top line-up of spooky shorts and features to one of the world’s most haunted cities–York,…

Hi, I have a borderline obsession with Japanese showa-era culture with much of my free time spent either consuming or researching said culture. Apparently I’m now writing about it as well to share all the useless knowledge I have acquired after countless hours surfing the web and peeling through books and magazines.